The Forrester Wave™: Cybersecurity Risk Ratings Platforms, Q2 2024

School District Attack Illustrates Ongoing Threat of Ransomware to Public Education

Interested in reading the report later? Download it.

Download Now

Executive Summary

- After a large U.S. school district recently announced that it had suffered a ransomware attack, SecurityScorecard consulted in-house data and strategic partnership sources to enrich the public reporting on the incident.

- Many of the issues SecurityScorecard’s ratings platform found to affect this district reflect our previous insights into common issues facing ransomware victims, including some that have affected K-12 institutions.

- Researchers identified a ransomware-linked file that may have been involved in the attack and discovered traffic that may reflect its distribution to a school district IP address. SecurityScorecard uncovered additional malicious files that may indicate that social engineering attacks against the school district preceded the deployment of ransomware.

- By combining findings from SecurityScorecard’s ratings platform with our network flow (netflow) data, researchers identified traffic that may indicate malware distribution, command-and-control (C2) communications, or data theft from district IP addresses.

Background

A large U.S. school district recently announced that it had suffered a ransomware attack. As with another recent attack against a school district, the announcement acknowledged that the incident caused significant disruption to its internal systems, though it additionally noted that it would not interrupt instruction when classes resumed. The initial announcement dids not discuss the possibility of a data breach, but subsequent guidance directing employees and students to reset their passwords seems to indicate the possibility that the attack exposed district credentials. Following this announcement, SecurityScorecard consulted in-house data and strategic partnership sources to enrich the public reporting on the incident. Drawing upon our ratings platform, network flow (netflow) data, and public cybersecurity resources (chiefly VirusTotal), we identified malicious files that threat actors may have used prior to and during the deployment of ransomware on district systems, traffic that may reflect malware distribution and data theft, and a number of vulnerabilities and other issues that our research has found to affect other ransomware victims in the past.

Platform Findings Most Prevalent Among Ransomware Victims

Many of the issues SecurityScorecard found to affect the district in our ratings platform mirror our findings regarding other ransomware victims, including education service providers whose breaches exposed school districts’ data.

SecurityScorecard has previously researched the links between our scorecard factors and ransomware attacks to identify which of the issues we observe are more prevalent among ransomware victims than in other organizations. That research compared a ransomware cohort comprising 126 organizations that had, based on public reporting or their appearance in a ransomware group’s leak site, experienced a ransomware attack in early 2021 to a control group (the “non-ransomware cohort”) made up of 140,000 organizations whose scorecards are monitored by at least two other companies on the SecurityScorecard platform and who did not appear in reports identifying ransomware victims. Many of the issue types identified in this research also affect this school district. Exposed personal information was almost 40% more prevalent among ransomware victims than in non-victim organizations; this particular victim organization’s scorecard revealed 162 findings in the exposed personal information category. Ransomware groups also often leverage previously-exposed account information for initial access to victim systems; most recently, CISA warned on September 8, “…[threat] actors obtain initial network access through compromised valid accounts.”

The platform currently records 626 findings of district devices running outdated operating systems and many devices (more than 11,000) running outdated web browsers. It is unclear whether these findings pose a risk to this school district’s operations in particular; large organizations like the school district often provide internet access and bring-your-own-device (BYOD) networks, which may help isolate vulnerable personal devices from operational assets. It is difficult to determine where these issues reside without knowing their network architecture and what protections are in place between operational and unmanaged assets. In general, though, these findings do appear more common in ransomware victims: the outdated_os and outdated_browser findings were, respectively, 24% and 22% more prevalent among ransomware victims than in other organizations.

The platform has also observed a group of related TLS issues affecting district resources: TLS services were observed supporting weak protocols at sixty assets, TLS services supporting weak cipher suites were observed at eighteen, one service was observed using a self-signed certificate, a certificate was observed with a validity period longer than dictated by the CAB forum’s baseline requirements, and one certificate was observed without revocation controls. These findings (tls_weak_cipher finding, tlscert_no_revocation, tls_weak_protocol, tlscert_self_signed, and tlscert_excessive_expiration) were, respectively, 30%, 29%, 23%, 26%, and 23% more prevalent among ransomware victims than the control group in our earlier research.

While ransomware operations may not exploit these specific issues, their higher prevalence among victims than non-victims may suggest that organizations affected by these issues face increased risks from ransomware; they may indicate a generally weaker cybersecurity posture.

Previous Issues: the Illuminate Education Third-Party Breach and the School District

Our earlier research has suggested that third-party breaches would likely remain a threat to educational institutions’ data. Prior to this attack, such a breach affected this same district: in May 2022, Illuminate Education, Inc. filed a breach notification with a state Attorney General’s office on behalf of this district, noting that an unauthorized party was able to access data belonging to students at many Illuminate client school districts (including this recent victim) between December 28, 2021, and January 8, 2022.

Illuminate Education announced in January that service disruptions reported by customers resulted from an unspecified security incident. Even after that incident, SecurityScorecard’s platform indicated that Illuminate suffers from issues attackers (including ransomware operators) could exploit. Previous leaks have exposed personal information belonging to employees, and attackers could use it to craft compelling phishing messages; ransomware attacks have often used employee credentials (like passwords that employees use across different accounts and fail to change after their exposure in a breach) to access target systems. Illuminate could also be susceptible to phishing attacks: the SPF record for one Illuminate Education subsidiary, IO Education, indicated a misconfiguration. SPF can help prevent email spoofing, but in its absence, threat actors can more easily craft and distribute phishing emails that can be more convincing because they appear to have originated from within a target organization. Software in use on June 20 and 21 at Illuminate-attributed IP addresses also appeared to be affected by high-severity vulnerabilities first identified in 2016 and 2018, which could indicate patch management issues that could be especially concerning given that ransomware often exploits unpatched vulnerabilities. Other issues, while not necessarily targeted by ransomware groups, may suggest a weaker overall cybersecurity posture and could therefore indicate an ongoing risk.

SecurityScorecard’s research into the links between our scorecard factors and ransomware attacks also revealed ransomware-correlated issue types affecting Illuminate Education. Like this district, Illuminated Education’s scorecard found it to be affected by exposed personal information (almost 40% more prevalent among the victims of ransomware than non-victim organizations) and TLS services that support weak protocols (30% more prevalent among ransomware victims than non-victims). SecurityScorecard’s research also noted that an additional TLS flaw that did not affect the current victim district, Certificate Without Revocation Control, affected Illuminate; this was 29% more prevalent in the ransomware cohort than in the control group. These findings suggest that Illuminate Education shares a profile with many ransomware victims, even if Illuminate Education did not identify the security incident discussed in its breach notice as a ransomware attack.

There is the additional possibility that the Illuminate Education breach could have exposed district employee data in addition to students’ information. Such an exposure could have supported the subsequent attack on this district. Attackers could have re-used credentials it exposed in attempts to access school district systems or incorporated exposed personal information into spearphishing lures tailored to certain target employees. Speaking more generally, though, alongside the more recent incident that targeted district employees directly, the Illuminate breach suggests that ransomware will continue to represent both a first- and third-party risk to K-12 education.

Platform Findings for Netflow Analysis

Researchers also used SecurityScorecard’s platform to guide their collection of network flow (netflow) data upon the above IP addresses. The IP addresses suffering from malware infections, high-severity vulnerabilities, and exposed database management systems (DBMS) would likely be low-hanging fruit for a threat actor and are, therefore, more likely to have been targeted as part of the recent ransomware attack. SecurityScorecard thus prioritized traffic involving them when collecting netflow data, given that our netflow tool limits the number of IP addresses a user can query when collecting traffic.

Communications indicative of malware infections were observed over the last 30 days at four district-attributed IP addresses. Evidence collected by our ratings platform indicates that three of these IP addresses suffer infections with the Bedep trojan or other malware resembling it. Researchers observed Bedep downloading second-stage malware and distributing ransomware to infected systems as early as 2015; traffic between these infected district addresses and other suspicious IP addresses discussed below could therefore indicate such activity or may additionally suggest C2 communications or data theft.

Ransomware groups often exploit unpatched CVEs. For example, CISA’s new alert about one group’s targeting of the education sector warns, “[threat] actors exploit vulnerabilities in an internet-facing systems [sic] to gain access to victims’ networks.” We observed ten high-severity vulnerabilities affecting two IP addresses during our last scan, which may still be publicly exposed. We observed these vulnerabilities:

- CVE-2021-44790

- CVE-2022-23943

- CVE-2021-39275

- CVE-2022-22720

- CVE-2021-26691

- CVE-2022-31813

- CVE-2015-1762

- CVE-2019-0211

- CVE-2015-1763

Given the possible targeting of these vulnerable IP addresses, researchers also included them in their netflow collections.

Finally, SecurityScorecard observed Microsoft SQL Server, a database management system (DBMS), publicly exposed at one IP address. DBMSes are attractive targets to attackers due to the data they may contain. An attacker that breaches a DBMS may sell the databases within, use them for extortion, or employ the information when launching further attacks. Exposed DBMSes could also make it easier for ransomware groups to exfiltrate data for secondary extortion. CISA’s recent warning about the Vice Society group’s targeting of education notes that the “actors are known for double extortion, which is a second attempt to force a victim to pay by threatening to expose sensitive information if the victim does not pay a ransom.” This may suggest that findings like this one may be particularly relevant to educational institutions.

VirusTotal Findings

In addition to SecurityScorecard’s internal datasets, researchers consulted sources from the broader cybersecurity community to identify additional evidence of recent malicious activity targeting this school district. Researchers identified a ransomware-linked file that may have been involved in the attack, along with other likely malicious files containing the district’s domain that may have facilitated the attack by granting attackers remote access to school district systems or enabling data theft and delivery of second-stage malware. The traffic represented by our netflow data (discussed at length below) may reflect activity involving these files.

One ransomware-linked file containing a district subdomain was submitted to VirusTotal on August 16. It is identified by the SHA-256 hash a13195c0d252ebbf1618c069d62c9d4e373295fd9bf9b6b236b6ff06c6663f6d and two vendors detect it as W32/PossibleThreat and Ransom.MSIL.Gorf. As the “Ransom” in Ransom.MSIL.Gorf, the cybersecurity community uses this designation to track a variety of ransomware active since at least 2018. One flow in the netflow data we collected may reflect the distribution of this file. The file is 497.12 MB, and our netflow data records one transfer of that size: on August 20, a DigitalOcean IP address, 165.227.29[.]171, sent 4971222 bytes (or 497.12 MB) to one of the district IP addresses suffering from a trojan infection.

This transfer could be a later-stage infection with the ransomware payload responsible for encrypting victim systems after a longer period of preparatory activity. In addition to our platform’s observation of an infection with a Trojan at this IP address, the other suspicious files and flows discussed below (many of which were observed before August 20) may represent infections with trojans or other malware that may have served to steal information or download second-stage payloads.

Fifty-one vendors have linked one such file, tracked by the SHA-256 hash 2fd20f17655b75b1230b8e01bf8aacae54c02f3497ead4a520df59263c225d22, to malicious activity, detecting it as, among other things, Trojan:Win32/Azorult.XT!MTB, Trojan-Downloader.Win32.Deyma.ya, and TR/Dropper.Gen. Like these examples, most other designations identify it as a Trojan, likely one related to the Azorult strain of malware, given the “Azorult” in the Trojan:Win32/Azorult.XT!MTB designation above. Trojan-Downloader.Win32.Deyma.ya and TR/Dropper.Gen may additionally indicate that it delivers additional malware to infected devices, as “downloader” and “dropper” refer to a trojan intended to deliver secondary payloads. This file first appeared on VirusTotal on July 14 and contacted a district subdomain.

SecurityScorecard uncovered additional malicious files that may indicate that social engineering attacks against the school district preceded the deployment of ransomware. A collection of fifty-four HTML files with embedded javascript, which may have been involved in an earlier stage of compromise culminating in the encryption of this school district’s systems, appeared on VirusTotal throughout July and August. These files either contain district URLs or email addresses (we have removed the specific domains, email addresses, and other identifying information about employees, but please contact us if you think you may be affected). Vendors have detected them as a variety of trojans, with Trojan.WIN32.cryxos.5913 being a particularly common detection.

Cryxos is a family of malicious javascript files that display fraudulent alerts to users visiting the malicious or compromised web pages hosting those files. These files typically enable tech support scams: they warn the user that their computer has been infected by a virus and direct them to call a threat actor-controlled telephone number. Usually, the attackers will take the call as an opportunity to collect payment information from the victim, framing it as legitimate payment for their “services” (their assistance removing a non-existent virus from the victim’s computer). However, in some cases, attackers will use the call to direct the victim to install software that gives the attackers remote access to their computer. Given this behavior, we can then speculate that in the case of this school district, attackers were able to obtain remote access to systems when a school district employee called the number displayed in a warning that appeared when they visited the webpage of a school in the district and installed remote-access software as directed by attackers masquerading as support personnel. That being said, it is also possible that attackers opportunistically injected the malicious javascript code into the district websites after the initial compromise. They could, for example, have taken the compromise as a chance to extract funds in as many ways as possible and used their newfound access to district resources to attempt tech support fraud against visitors to school district websites, which would likely be experiencing heavy traffic around the time of the attack, which coincided with the beginning of the school year.

A list of the SHA-256 hashes for all of these HTML files is available in an appendix, but the following sample of some of the most recently submitted files in this group should offer a representative overview of the common details.

The file identified by the SHA-256 hash 31053e5a870b5bcdf429bb413e11738eac12c0c6ec6d9c058e763ba6b7ece2df appeared on VirusTotal on August 31. Two vendors detect it as Trojan.WIN32.cryxos.5913 and Malware.Generic-HTML.Save.d67738cd, it links to two district URLs, and it contains a staff member’s email address.

The file identified by the SHA-256 hash e4624f2a4aebcaa9b224eb6b6a2510c2057f09209eba66ced576dfc01c98cfc9 first appeared on VirusTotal on September 5. One vendor detects it as Trojan.WIN32.cryxos.5913. Its title indicates that it is a school’s webpage, while a link it contains suggests that the titular school is one within the affected district.

The files identified by the SHA-256 hashes 44a9795bc825d7c8937979f53869a8f2b63b9a2399519eec65e057a68dabd305 and D9af65f7138f1c2a83e24af8d56b86187cffd0a2ae26092129d43ff65413273b both appeared on VirusTotal on September 6. Three vendors detect the former as Detected, Trojan.Script.GenericZ, and Trojan.WIN32.cryxos.5913, and it links to two district URLs. One vendor detects the latter as Trojan.WIN32.cryxos.5913, and it is titled “TEACHING WITH THE STUDENT AT THE CENTER, NOT THE SUBJECT,” which appears to come from a website belonging to a district employee.

The file identified by the SHA-256 hash D454fb1ace8586893e734fadb2c20b492a275bda532968299c1cd2a79f8d1716 appeared on VirusTotal on September 8. One vendor detects it as Trojan.WIN32.cryxos.5913, and it contains a district email address.

Netflow Analysis

SecurityScorecard’s previous research into ransomware attacks against local governments and educational institutions has noted that threat actors’ dwell times are increasing. The submission dates of the files above also suggest malicious activity may have begun in July. Hence, researchers sampled netflow data from a fairly large window, collecting traffic from July 6 to September 6.

Using SecurityScorecard’s access to exclusive network flow (i.e. netflow) data, researchers were able to identify suspicious traffic between district assets and other IP addresses throughout July and August, which could be connected to the recent attack. Some of the data transfers from suspicious IP addresses to school district IP addresses could indicate malware distribution, the back-and-forth data exchanges between these IP addresses could indicate C2 communications, and the large transfers of data from district-attributed IP addresses to suspicious IP addresses could indicate exfiltration.

It does bear noting, though, that some of this traffic could be benign. For example, many of the IP addresses discussed below belong to DigitalOcean. Because DigitalOcean provides various services, many of which are legitimate, it is possible that the transfers discussed below do not represent malicious activity. For example, the many large transfers from DigitalOcean IP addresses to district IP addresses discussed below could indicate data transfers to the school district from backups. However, knowing that the school district suffered an attack, this traffic (especially traffic involving the IP addresses that other vendors have already deemed malicious) likely merits additional scrutiny. Without internal visibility into the district’s network, SecurityScorecard cannot confirm that these flows indicate malicious activity, but if school district employees can access them, SIEM logs would likely offer the necessary information to make a more thorough assessment.

Researchers observed an unusually large number of netflows involving port 8888. This traffic first attracted researchers’ attention due to the number of flows involved. While 553 flows of 9,665 is still a relatively small fraction, it is a larger proportion than usual in our netflow collections. This traffic may additionally be suspicious because various malware strains have been observed communicating over port 8888. Those flows involving communication over port 8888 featured twenty-nine unique, non-district IP addresses. All but one of the addresses, 198.12.158[.]38, belong to DigitalOcean, and other vendors have linked nine of the twenty-nine to malicious activity. More detail is available in the appendix below, but these flows indicated repeated communication and large data transfers between possibly malicious IP addresses and district assets where our ratings platform has observed malware infections. In light of the size of the observed transfers and given the IP addresses’ possible links to malicious activity and SecurityScorecard’s findings indicating that the school district IP addresses suffered from malware infections within the same timeframe as these transfers, these flows may indicate malware distribution, communication with command-and-control (C2) infrastructure or data exfiltration.

Forty flows of one GB or more involving twenty-nine unique, non-district IP addresses also took place. The full list is available in the appendix below, but of those IP addresses, vendors have linked two, 184.106.54[.]10 and 192.241.210[.]229, to malicious or suspicious activity. A school district-attributed IP address, 12.207.133[.]197, made four transfers to 184.106.54[.]10 on July 13, August 10, and August 19. The largest of these, which transferred 3.55 GB, occured on July 13. One vendor has linked 184.106.54[.]10 to malicious activity, as have two members of the VirusTotal community. Given the size of the observed transfers and 184.106.54[.]10’s possible links to malicious activity, along with the high-severity CVEs affecting 12.207.133[.]197 (see above), it is possible that these flows indicate data exfiltration. 144 flows between 192.241.210[.]229 and 204.108.115[.]35 took place between July 7 and August 16. These ranged in size from 486.82 KB to 4.29 GB. The largest (4.29 GB) transfer occured on July 7; 192.241.210[.]229 sent that data to a district IP address. One vendor has linked 192.241.210[.]229 to malicious activity, another deems it suspicious, and fifteen VirusTotal community members have linked it to attempted exploitation of the Log4J vulnerability, brute force attacks, and communication with HTTP and HTTPS honeypots. In light of the size of the observed transfers and given 192.241.210[.]229’s possible links to malicious activity and SecurityScorecard’s findings indicating that the district IP address suffered from a malware infection within the same timeframe as these transfers, these flows may indicate malware distribution, communication with command-and-control (C2) infrastructure, or data exfiltration.

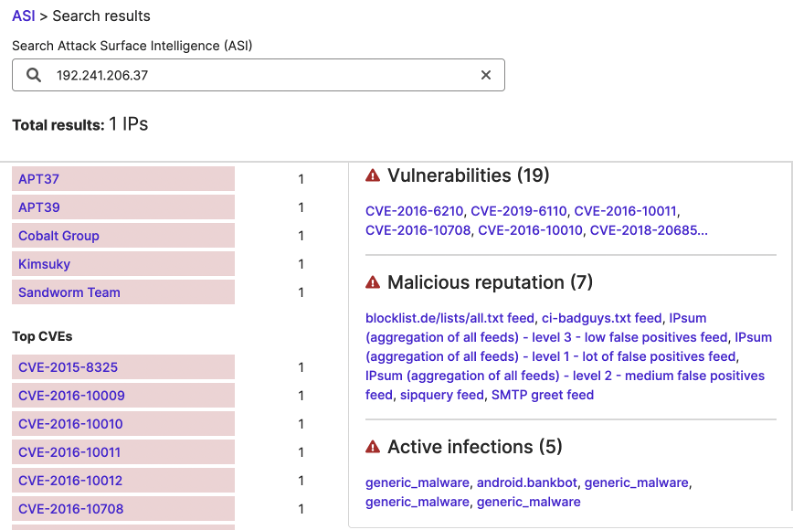

Recognizing that open DBMS ports can be easy targets for data theft, researchers also focused their analysis of netflow dataset on traffic involving 104.42.219[.]40, the school district-attributed IP address where SecurityScorecard observed Microsoft SQL Server publicly exposed. Of the 129 flows featuring it, one may indicate exfiltration: on August 27, the school district transferred 14.04 MB to 192.241.206[.]37, which five vendors have linked to malware and malicious activity and which ten members of the VirusTotal community have linked to malware, SSH brute force attacks, and possibly malicious traffic to honeypots. The malicious reputation feature of SecurityScorecard’s ASI tool also links it to malicious activity.

This transfer, however, may just be the culmination of a compromise begun earlier. Between July 6 and September 3, 129 flows involving thirty-three non-district IP addresses took place. Of those, other vendors have linked a majority (twenty-four) to malicious or suspicious activity. Those addresses are available in the appendix below.

Conclusion

Although these conclusions must remain hypothetical in the absence of internal visibility into the school district’s systems, the above findings indicate that malicious activity targeting the school district occurred beginning in July, and that infections with trojans of various sorts preceded the deployment of malware against the district. SecurityScorecard’s ratings platform has revealed this district to suffer from several vulnerabilities that have affected other ransomware victims in the past and indicates that it suffered from infections with malware that could have downloaded subsequent malicious payloads. Such activity could have culminated in the encryption of the district’s systems. Researchers additionally identified what appears to be a series of infections with malicious javascript on district webpages, both preceding and following the announcement of the attack. Some of these infections could also have led earlier social engineering targets to grant attackers remote access to district devices. SecurityScorecard also observed a ransomware-link file containing the district’s domain and traffic within our netflow data that may reflect the distribution of all of the above malware and could additionally reflect the exfiltration of data from the school district’s network.

This information was gathered and analyzed to briefly preview some of SecurityScorecard’s threat intelligence and investigation capabilities. SecurityScorecard was only able to query and contextualize some of its in-house sources; it, therefore, bears noting that this is not an exhaustive list of issues related to the school district’s overall cyber risk exposure. However, the data researchers have collected and analyzed thus far may offer new insights into the attack and the ransomware-related issues facing the school district.

Next Steps: Mitigation and Remediation

Shortly after the announcement of this attack, the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) circulated a new warning regarding ransomware targeting the education sector. While the specific ransomware group named in that warning may not be responsible for this particular attack, the guidance it provides will help reduce the risks of ransomware attacks. These recommendations include improvements to monitoring and logging of network activity, improved account protection through the strict application of multi-factor authentication (MFA), attentive management of internal infrastructure, and thorough remediation planning. SecurityScorecard’s offerings can support organizations in many of these areas.

Professional Services

SecurityScorecard’s services can support organizations before and after ransomware incidents.

The active security services we offer prior to an attack include penetration testing, tabletop exercises, and red-teaming, all of which can support remediation planning.

SecurityScorecard’s threat research and intelligence could be the competitive advantage educational institutions need to stay ahead of today’s fast-moving threat actors. For more custom insights from our team with 100+ years of combined threat research and investigation experience, or more details on these findings, please contact us to discuss our Cyber Risk Intelligence as a Service (CRIaaS) offering. The above investigation can offer a trustworthy but preliminary view of our capabilities. Our team can continue diving into these details, especially with the ability to provide further support by working with on-site staff.

Should an attack occur, SecurityScorecard also provides managed incident response and digital forensics teams as a professional service driven by a large group of former law enforcement and private sector experts with decades of experience in the space. For immediate support from our teams, please contact us.

Attack Surface Intelligence

SecurityScorecard’s new Attack Surface Intelligence (ASI) solution gives you direct access to SecurityScorecard’s deep threat intelligence data through a global tab on the ratings platform and via API, all of which can contribute to improved visibility into internal and external resources, supporting the infrastructure management advised above.

ASI analyzes billions of sources to provide deep threat intelligence and visibility into any IP, network, domain, or vendor’s attack surface risk, from a single pane of glass. This helps a variety of customers do more with the petabytes of data that form the basis of SecurityScorecard Ratings, including identifying all of an organization’s connected assets, exposing unknown threats, conducting investigations at scale, and prioritizing vendor remediation with actionable intelligence.

ASI is built into SecurityScorecard’s ratings platform through an enhanced Portfolio view or Global search across all Internet assets, leaked credentials, and infections and metadata from the largest malware sinkhole in the world. Access ASI today through our Early Access program by filling out the demo request form or by contacting ASI.

Blueprint for Ransomware Defense

On August 4, the Institute for Security and Technology’s (IST) Ransomware Task Force (RTF) announced the release of its Blueprint for Ransomware Defense – a clear, actionable framework for ransomware mitigation, response, and recovery aimed at helping organizations navigate the growing frequency of attacks.

SecurityScorecard is proud to be the only security ratings platform to sponsor and participate in the development of The Blueprint, and is one of only five organizations that participated in the program’s development.

You can see the Blueprint for Ransomware Defense here.

Appendix: IP Addresses Observed Communicating Over Port 8888

Those flows involving communication over port 8888 featured twenty-nine unique, non-district IP addresses:

- 138.197.174[.]102

- 157.230.96[.]164

- 192.241.192[.]25

- 198.199.110[.]173

- 138.68.237[.]164

- 198.199.105[.]118

- 146.190.228[.]2

- 192.241.193[.]195

- 198.199.103[.]51

- 198.199.98[.]111

- 192.241.200[.]18

- 192.241.197[.]213

- 142.93.145[.]243

- 198.12.158[.]38

- 165.227.51[.]196

- 167.71.160[.]135

- 165.22.59[.]29

- 137.184.149[.]49

- 198.199.112[.]252

- 165.227.14[.]26

- 198.199.114[.]182

- 138.68.56[.]94

- 198.199.109[.]11

- 159.65.87[.]65

- 192.241.210[.]64

- 137.184.169[.]95

- 138.197.169[.]151

- 138.197.177[.]215

- 138.68.107[.]86

All but one of the above addresses (198.12.158[.]38,) belong to DigitalOcean. Other vendors have linked nine (including 198.12.158[.]38) to malicious activity.

- 192.241.193[.]195

- Twenty-three flows between 192.241.193[.]195 and district IP addresses took place on July 20 and August 23.

- The first of these was the only one to occur on July 20 or involve port 8888. It transferred 13.1 MB from port 8888 at 192.241.193[.]195 to port 14600 at a district IP address.

- All of the other flows took place on August 23 using port 443 at 192.241.193[.]195 and port 1482 at another district IP address and involved data transfers ranging in size from 486.82 KB to 14.35 MB.

- Three other vendors have linked 192.241.193[.]195 to malware or other malicious activity and one VirusTotal community member has observed it connecting to an HTTP or HTTPS honeypot.

- In light of the size of the observed transfers and given 192.241.193[.]195’s possible links to malicious activity and SecurityScorecard’s findings indicating that the school district IP suffered from a malware infection within the same timeframe as these transfers the exchanges of data on August 23 may indicate malware distribution, communication with C2 infrastructure or data exfiltration.

- Twenty-three flows between 192.241.193[.]195 and district IP addresses took place on July 20 and August 23.

- 198.12.158[.]38

- 198.12.158[.]38 contacted one school district IP address at port 8888 once on August 2. This was likely low-level scanning activity. Only one flow took place, transferring a small amount of data. The district IP address does not appear to have responded, and as of September 6, SecurityScorecard’s Attack Surface Intelligence (ASI) tool indicates that port 8888 is not open at that IP address.

- 198.12.158[.]38 has also appeared in four other SecurityScorecard investigations, where it exhibited similar behavior, making small, infrequent transfers that do not appear to have received responses.

- Eight vendors have linked 198.12.158[.]38 to malicious activity or malware. It also appears in three VirusTotal community members’ collections, including one noting that it had connected to an HTTP or HTTPS honeypot.

- 198.12.158[.]38 contacted one school district IP address at port 8888 once on August 2. This was likely low-level scanning activity. Only one flow took place, transferring a small amount of data. The district IP address does not appear to have responded, and as of September 6, SecurityScorecard’s Attack Surface Intelligence (ASI) tool indicates that port 8888 is not open at that IP address.

- 192.241.210[.]64

- Thirteen flows between 192.241.210[.]64 and a district IP address, 204.108.115[.]124, took place on July 13 and August 28.

- The school district IP address transferred 374.38 KB to port 8888 at 192.241.210[.]64 on July 13.

- All of the other flows took place on August 28 and involved data transfers ranging in size from 486.82 KB to 14.76 MB.

- Two vendors have linked 192.241.210[.]64 to malware or malicious activity and one VirusTotal community member has observed it connecting to an HTTP or HTTPS honeypot.

- In light of the size of the observed transfers and given 192.241.210[.]64’s possible links to malicious activity and SecurityScorecard’s findings, indicating that the district IP address suffered from a malware infection within the same timeframe as these transfers. These flows may indicate malware distribution, communication with C2 infrastructure, or data exfiltration.

- Thirteen flows between 192.241.210[.]64 and a district IP address, 204.108.115[.]124, took place on July 13 and August 28.

- 137.184.169[.]95

- The same district IP address as in the above flows first contacted 137.184.169[.]95 at port 8888, making a 156 KB-transfer on July 13.

- Then, on July 26, 137.184.169[.]95 sent 306 KB to 204.108.115[.]124 over UDP and, in a possible response, 204.108.115[.]124 made two transfers (one of 327.68 KB and one of 156 KB) to 137.184.169[.]95 over TCP on the same date

- One vendor has linked 137.184.169[.]95 to phishing.

- The same district IP address as in the above flows first contacted 137.184.169[.]95 at port 8888, making a 156 KB-transfer on July 13.

- 192.241.192[.]25

- Fifty-eight transfers ranging in size from 486.82 KB to 41.42 MB took place between 192.241.192[.]25 and the school district on July 13.

- Four vendors have linked 192.241.192[.]25 to malware or malicious activity.

- In light of the size of the observed transfers and given 192.241.192[.]25’s possible links to malicious activity and SecurityScorecard’s findings indicating that the involved school district IP address suffered from a malware infection within the same timeframe as these transfers, these flows may indicate malware distribution, communication with command-and-control (C2) infrastructure or data exfiltration.

- 138.68.237[.]164

- 138.68.237[.]164 first contacted a school district asset on July 7, when it transferred 1.14 MB to it.

- Then, on July 13 and 14, another fourteen flows involving 138.68.237[.]164 occurred.

- A different school district IP address appears to have initiated this series of flows by making five transfers between 425.98 KB and 1.52 MB between 22:58:29 and 23:00:18 UTC on July 13.

- The two IP addresses subsequently continued to exchange data on July 14, with all of the flows on that date occurring between 04:56:50 and 04:58:56 UTC.

- Of these, two transfers from 138.68.237[.]164 may be particularly noteworthy due to their size; it transferred 26.96 MB and 52.91 MB to the district at 04:56:50 and 04:57:10 UTC. This may indicate the delivery of additional malware after an initial compromise.

- One vendor has linked 138.68.237[.]164 to malware.

- In light of the size of the observed transfers and given 138.68.237[.]164’s possible links to malicious activity and SecurityScorecard’s findings indicating that the two school district IP addresses suffered from malware infections within the same timeframe as these transfers, these flows may imply malware distribution, communication with command-and-control (C2) infrastructure, or data exfiltration.

- 142.93.145[.]243

- Seventeen flows between 142.93.145[.]243 and a school district IP address occurred between 05:55:41 and 05:59:16 UTC on July 29.

- 142.93.145[.]243 appears to have initiated this exchange of data by transferring 33.98 MB to 204.108.115[.]196.

- It was more frequently a sender of data than recipient in the subsequent transfers, sending data in ten of the sixteen other flows.

- Transfers from 142.93.145[.]243 were also larger than transfers from the school district to it.

- The smallest transfer from 142.93.145[.]243 was 1.04 MB and the largest was 45.87 MB

- The smallest transfer from the district was 425.98 KB and the largest was 1.16 MB.

- 142.93.145[.]243 appears to have initiated this exchange of data by transferring 33.98 MB to 204.108.115[.]196.

- Five vendors have linked 142.93.145[.]243 to malware and malicious activity.

- In light of the size of the observed transfers and given 142.93.145[.]243’s possible links to malicious activity and SecurityScorecard’s findings indicating that school district suffered from a malware infection within the same timeframe as these transfers, these flows may indicate malware distribution, communication with command-and-control (C2) infrastructure or data exfiltration.

- Seventeen flows between 142.93.145[.]243 and a school district IP address occurred between 05:55:41 and 05:59:16 UTC on July 29.

- 165.227.51[.]196

- Eighty-five flows between 165.227.51[.]196 and the school district took place on July 6 and August 16.

- These ranged in size from 425.98 KB to 64.24 MB.

- 165.227.51[.]196 sent data more often than it received it and was responsible for most of the larger transfers (it was the sender for all flows larger than 12 MB).

- One vendor has linked 165.227.51[.]196 to malicious activity.

- In light of the size of the observed transfers and given 165.227.51[.]196’s possible links to malicious activity and SecurityScorecard’s findings indicating that the school district IP address suffered from a malware infection within the same timeframe as these transfers, these flows may indicate malware distribution, communication with command-and-control (C2) infrastructure or data exfiltration.

- Eighty-five flows between 165.227.51[.]196 and the school district took place on July 6 and August 16.

- 198.199.109[.]11

- Six vendors have linked 198.199.109[.]11 to malware and malicious activity and three VirusTotal community members have linked it to SSH brute force attacks and communication with a honeypot.

Appendix: Data Transfers of One GB or More

Forty flows of one GB or more involving twenty-nine unique, non-district IP addresses also took place. Those IP addresses are:

- 192.241.210[.]229

- 104.239.141[.]31

- 198.199.109[.]152

- 198.199.112[.]252

- 192.241.200[.]103

- 198.199.108[.]171

- 198.199.119[.]140

- 172.99.100[.]15

- 104.130.127[.]156

- 172.99.116[.]133

- 172.99.117[.]251

- 198.199.108[.]29

- 198.199.100[.]109

- 198.199.103[.]51

- 198.199.93[.]190

- 198.199.92[.]46

- 172.99.117[.]239

- 172.99.118[.]28

- 198.199.100[.]30

- 166.78.174[.]60

- 198.199.100[.]44

Of those IP addresses, vendors have linked two to malicious or suspicious activity:

- 184.106.54[.]10

- A school district-attributed IP address made four transfers to 184.106.54[.]10 on July 13, August 10, and August 19.

The largest of these, which transferred 3.55 GB, took place on July 13. - One vendor has linked 184.106.54[.]10 to malicious activity, as have two members of the VirusTotal community.

- In light of the size of the observed transfers and given 184.106.54[.]10’s possible links to malicious activity and the high-severity CVEs affecting the school district IP address, it is possible that these flows indicate data exfiltration.

- A school district-attributed IP address made four transfers to 184.106.54[.]10 on July 13, August 10, and August 19.

- 192.241.210[.]229

- 144 flows between 192.241.210[.]229 and a different school district IP address took place between July 7 and August 16.

- These ranged in size from 486.82 KB to 4.29 GB.

- The largest (4.29 GB) transfer took place on July 7; 192.241.210[.]229 sent that data to the district IP address.

- One vendor has linked 192.241.210[.]229 to malicious activity and another deems it suspicious.

- Fifteen VirusTotal community members have linked it to attempted exploitation of the Log4J vulnerability, brute force attacks, and communication with HTTP and HTTPS honeypots.

- In light of the size of the observed transfers and given 192.241.210[.]229’s possible links to malicious activity and SecurityScorecard’s findings indicating that the school district IP address suffered from a malware infection within the same timeframe as these transfers, these flows may indicate malware distribution, communication with command-and-control (C2) infrastructure, or data exfiltration.

- 144 flows between 192.241.210[.]229 and a different school district IP address took place between July 7 and August 16.

Appendix: Suspicious IP Addresses Communicating with the IP Address with Exposed DBMS

- 192.241.221[.]210

- 159.223.160[.]153

- 167.71.176[.]103

- 104.131.11[.]159

- 107.167.2[.]117

- 192.241.206[.]37

- 192.241.221[.]222

- 89.203.251[.]79

- 170.210.45[.]163

- 159.203.168[.]116

- 143.110.253[.]221

- 185.133.240[.]155

- 45.232.73[.]51

- 192.241.198[.]29

- 192.241.206[.]10

- 64.227.90[.]185

- 102.219.77[.]46

- 137.184.222[.]169

- 192.241.214[.]44

- 169.239.252[.]40

- 68.183.31[.]176

- 159.203.168[.]191

- 192.241.237[.]105

- 192.241.204[.]206

Appendix: SHA-256 Hashes of HTML Files Containing District Domain and Detected as Trojans

- 773db5c80898fa214918c4c25a350e03de44dd09d179f08686da4c0e90809f1f

- D454fb1ace8586893e734fadb2c20b492a275bda532968299c1cd2a79f8d1716

- Dab421f8a1bbd5119408866b00e1f3297b013ba76a2f35775f92c57906796775

- 9e523136dbcca217ddb67dba0a4a03396731fa78ea287d320cb8d10b6b8b7ed8

- d66626569ae8c25c5d00c770d64c573859e1464181b9aa15d74ff468f520c1a0

- 27383e1f9a43eb4ae6281b24e5bd69084cc0e02f12c1eb8cc79a88bd0b73a79d

- 31053e5a870b5bcdf429bb413e11738eac12c0c6ec6d9c058e763ba6b7ece2df

- 0fddeb7be75b837c0d3080209c41ab5d2b095e0de4d2024eaf15bfd634f92133

- ec8a535605ddaec0af8e26c07f129cdf70a2ccf4c47406e0bc0522c810a1cf7d

- 2c4af257ebe9ffe45ccc7752557b4b1497caa46d329e22e6c804219495986226

- fa3d62addad7cafec06268d3f0d1360d81cc51a9c7cb0e84aed6b300066143b8

- da06cbe20b0a60ea4257ff36ba67402d622c18153a7a684fa695bc60065291f7

- 66dbb04c4c17c76d3e1d845a932f0564e56630d5e81c58c28044180150aae624

- aded61d8f2422a63abe226a8e45a87dc5010a81b71de482b510430d8b49932c7

- ca25e1978320baf3349a006e9a1826d49f1c64bfb04c364a31d9c07b9d6ad54f

- 5d428edc8de70fec553130efb6d9ba44b62813cd7dba401c8a9b7211cea33b90

- 740d60020af897e1567108cd4660b01caa1dc5be613997363ac3e62351ba57e2

- 47a1e18f53f0d4473c53c4ab2697e1d12d90a889a4785c3416631f152d63619f

- 00259b37f9f8482f142159473d8aaf3170510cf9f437ddb80b06033973ab6f81

- da4792d3f35a6778492f91ea718b45faa6ad19eb206a4de279a362fed0eef2a7

- fb5a2d145f70dab6ed3cd3dba3871856d043a054f402f4579d0ef50104996c0f

- 2323cdfc4cc9855db27ec278606f59d9853d9e46833460331cffd7f2203668c6

- ffc85dfdd3aabdd141d0857434d9192a3a215b9be2ac0ae3f43a13603035ccb5

- f0b592da2812baf0b6ff69e3525563d3414f06198bf49e4bcd9b29f6614550a2

- 3ccf675348fa8edade8cecc263403eed7abe04f4f79665213f605a62bb195010

- a13195c0d252ebbf1618c069d62c9d4e373295fd9bf9b6b236b6ff06c6663f6d

- 18ad02607bdb722336f47ceff6864d1d8b7398665248a0ae861fd414f6ac6b9c

- 4c036c8c16e435a5cdb524dd0198ea74c3a08fbcdba21a31e3b72ab01d494e8f

- 45c46eddd47cd515e66d0bcd4079a991b07aefbd2e4c78766fbebdd330e29938

- b30d652d9ff41998f46352e25de71ef64cb1283630a5655fc96676d881362544

- 235dcb093d6c0cde5969dae64fc810ebdfa2bf5e1e040f8678eab35eae34d90d

- 4d22465cee1f6cf7f88f502be0b6da60242ac00276287185a5310a4682fb9675

- f5a5414091ce49a855c9244f9c877ba707620e7482dbf4d210b04263c1ea239a

- 3191a3603a253a05dcb0c4b4eae11e4111a2fbc7d956d7a887b122f31e72c1f8

- 483bd5d8976030cfaff83d3e09312fed40ff27cacebe8e3b0703bbc471e899ed

- 024b408a1b5ee3fe73908ef94abc5969b269c72d6272ad4f54ec65df33d553f3

- 21d1180359b53e7babfdfb87c68451c87eb28b0fa7d06c3007cf78af6283f6a0

- 1257d30ccecfa2962e162d554785cc96c086bd70391c83db705f6e8348176206

- cb2af69ff66e4217fa73ddf1bbb05cefcc9a313d3e21362cb9b841d6e00f2ceb

- 147d0880c6f9cb7b7cf2c1bb366e60d14eb7d6590265fa30470a587108f91ce9

- e650849771fe5ce5593aa2e2eef248a07626e10ef7d57db9625f9b5452498517

- 6dd2cc9eff2f2388b7c24c45071ef120176c418b22751919df305db591994ce9

- a439de0b215699969116871bcb72ce33d3ff8c2e6e93bf7d75c30094b6831d20

- bae82062b59d53e761fc227e73083709ffbca2a7efd6af7c2fb3b0811a53799c

- 31d915dd3756e29bc4c2ba645bdd8dbda22886eb652f3326a45b6a26524af362

- 2fd20f17655b75b1230b8e01bf8aacae54c02f3497ead4a520df59263c225d22

- 0809f77037d10a4853815220549d4cd91c1200279783a37a9680d8d272482d6b

- 0b7f8cbf1dfebe67ad03fe71aaa3ed8872482a5c64b5384b121eb008c19e85b3

- c1675426ab30ae7ea2c71655c9e67eb040c5ad357fe79973bf6cd745aa52f90b

- 44a9795bc825d7c8937979f53869a8f2b63b9a2399519eec65e057a68dabd305

- D9af65f7138f1c2a83e24af8d56b86187cffd0a2ae26092129d43ff65413273b

- e4624f2a4aebcaa9b224eb6b6a2510c2057f09209eba66ced576dfc01c98cfc9

- D66626569ae8c25c5d00c770d64c573859e1464181b9aa15d74ff468f520c1a0

- 60fa5a7b352431f0c77eb6a554342cf175501b5600231ece7b3d197b34f0feec