Brute Force Attempts May Have Preceded Ransomware Attack on School District

Executive Summary: Vice Society Ransomware Group Attack

- Following reports that an attack by the Vice Society ransomware group was responsible for disrupting a US school district’s operations, SecurityScorecard researchers reviewed available data from internal sources and strategic partnerships.

- SecurityScorecard’s platform revealed that the school district suffered from issues that our previous research found common among ransomware victims.

- SecurityScorecard’s network flow (netflow) analysis suggested that the school district suffered a series of possible SSH brute force attacks in June and July. Our Attack Surface Intelligence (ASI) tool identified open ports that may have been vulnerable to such attacks.

- These attacks may represent a novel tactic on Vice Society’s part.

Background of Brute Force & Ransomware Attacks on School Districts

Vice Society Ransomware Group

According to research into the group conducted by Sekoia and published in July 2022, the Vice Society ransomware group first appeared in May 2021 and has targeted educational institutions quite heavily; more of its victims have been in the education sector than any other. Early research into the group suggested that it was a successor to the HelloKitty ransomware, with one researcher noting similarities between the groups’ encryption methods as early as June 2021. However, Sekoia’s more recent research suggests that Vice Society simply uses strains that are relatively easily available through ransomware-as-a-service operations that have historically been advertised fairly widely in the Russian-speaking cybercriminal underground, including the HelloKitty and, more recently, Zeppelin strains of ransomware (Zeppelin was itself the subject of a recent CISA alert). The Zeppelin strain first became available in Russian cybercrime forums in 2019 and has appeared in more recent Vice Society attacks. While the group attracted attention early on in its operations for exploiting the then-novel PrintNightmare vulnerability, the extant public research has not linked Vice Society to SSH brute force attacks, so the activity described below may represent a dimension of the group’s attacks not previously reported.

SecurityScorecard Findings

SecurityScorecard’s platform has observed issues (including configurations) affecting the school district’s assets that are common among ransomware victims according to previous SecurityScorecard research.

SecurityScorecard found an open FTP service at an IP address attributed to the school district as recently as August 2. Generally speaking, attackers may take an interest in file-sharing services because they offer a means of accessing victim data. Some ransomware groups have taken a particular interest in it. For example, Sophos warned in February 2021 that it had observed the Conti group using FTP to steal victim data.

SecurityScorecard also noticed five high-severity vulnerabilities affecting the versions of the SSH software running at port 22 of four school district IP addresses between July 20 and August 7. The vulnerabilities in question are CVE-2010-4478, CVE-2016-10009, CVE-2016-8858, CVE-2016-10012, and CVE-2016-6515. A remote attacker could exploit CVE-2010-4478 to bypass certain access controls and authenticate to a system, leverage CVE-2016-10009 to execute arbitrary code on affected systems, and escalate privileges through exploiting CVE-2016-10012.

Meanwhile, CVE-2016-6515 and CVE-2016-8858 are both vulnerabilities attackers could exploit to deny service through affected versions of OpenSSH. These vulnerabilities may be particularly concerning in light of the recent attack not only because Vice Society has, in general, been known to exploit published vulnerabilities (especially for remote code execution, which CVE-2016-10009 can allow) and because these vulnerabilities affect software running at the ports involved in the suspicious traffic uncovered by SecurityScorecard’s netflow analysis, but also because, more generally, some attacks with the Zeppelin strain (which Vice Society has employed recently) have exploited vulnerabilities in public-facing applications for initial access.

SecurityScorecard also observed exposed credentials, which an adversary could use to launch credential-stuffing attacks; these may have been the particular variety of brute force attack suggested by the traffic discussed below. SecurityScorecardhas observed 11 information leaks that exposed 239 passwords associated with school district email addresses, which attackers could have employed in the SSH attacks discussed below. In some cases, these leaks also contained employees’ personal information, including names, dates of birth, password hints, job titles, and physical addresses. These latter categories pose a less direct threat than exposed passwords. Nonetheless, they represent a significant risk, as attackers could use them to mount social engineering attacks against the employees in question and then use information acquired from them to attack the school district.

Beyond the possible avenues of attack enabled by the issues discussed above, SecurityScorecard has previously researched the links between our scorecard factors and ransomware attacks in order to identify which of the issues we observe are more prevalent among ransomware victims than other organizations. Many of the issue types identified in this research also affect the school district in question.

SecurityScorecard observed seventeen cases of exposed personal information affecting school district employees. This issue was almost 40% more prevalent among the ransomware cohort than among non-victim organizations. SecurityScorecard observed TLS services that support weak protocols in use on the district’s networks; this finding is over 30% more prevalent among ransomware victims than non-victims. Our earlier research also noted that another TLS flaw, TLS Service Supports Weak Cipher Suite, was 30% more prevalent in the ransomware cohort than in the control group. SSC has found services at district-attributed IP addresses to support weak cipher suites. While these findings may not clearly illustrate the path attackers took to compromise the school district’s systems, they may indicate that the district suffers from issues common to ransomware victims. In order to better focus their efforts to collect network flow (netflow) data likely to yield insights about the attack against the school district, our researchers used its scorecard’s findings to guide their data collections, limiting their netflow sample to traffic involving the four IP addresses where the SecurityScorecard’s platform detected the issues discussed above (207.191.197[.]62, 207.191.197[.]42, 207.191.197.41, and 72.52.219[.]120).

SecurityScorecard Netflow Analysis

SecurityScorecard’s netflow tool detected considerable traffic that may indicate a series of possible SSH brute force attacks against the school district. SecurityScorecard’s netflow tool observed 8,281 flows to the four IP addresses attributed to the school district over a monitoring period lasting from June 5 to August 5, 2022. Of those, a disproportionately large number (3,571) involved port 22, the standard port for SSH traffic. The dates with the five heaviest concentrations of traffic using port 22 were (in descending order by flow count) June 5, June 7, June 19, June 10, and July 1. As of August 5, ASI has also revealed that SSH was still in use at port 22 of the school district IP addresses involved in these flows.

June 5

The first possible attack appears to have occurred on June 5. Three school district-attributed IP addresses saw a relatively large number of flows (640) that used port 22 and involved the three aforementioned IP addresses attributed to the school district.

These flows involved 22 external IP addresses, all of which other vendors have linked to malicious activity:

159.65.240[.]232

188.166.181[.]167

167.99.61[.]176

104.248.157[.]240

128.199.251[.]65

165.22.240[.]154

27.109.12[.]34

31.220.17[.]31

41.63.9[.]36

159.65.154[.]92

103.4.119[.]20

167.71.131[.]111

68.183.142[.]49

139.59.168[.]22

161.35.127[.]34

165.22.49[.]42

159.223.61[.]129

137.184.215[.]32

128.199.145[.]5

164.92.150[.]6

165.227.167[.]225

167.71.204[.]59

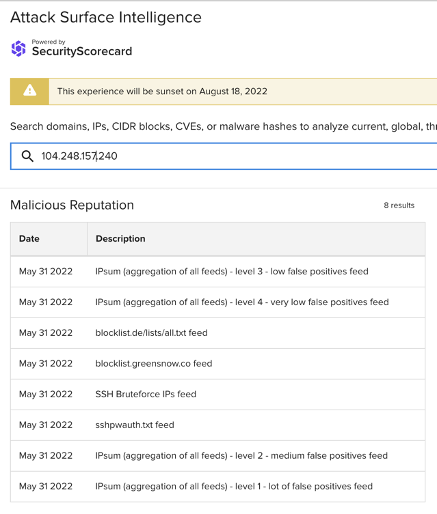

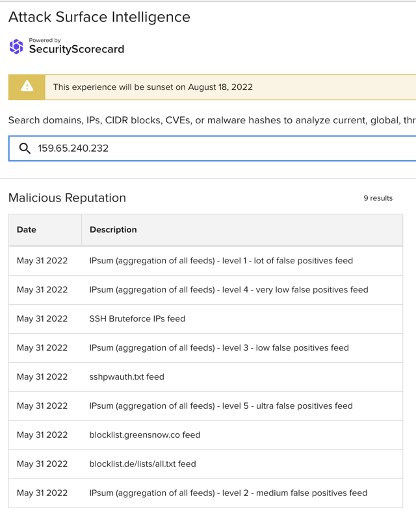

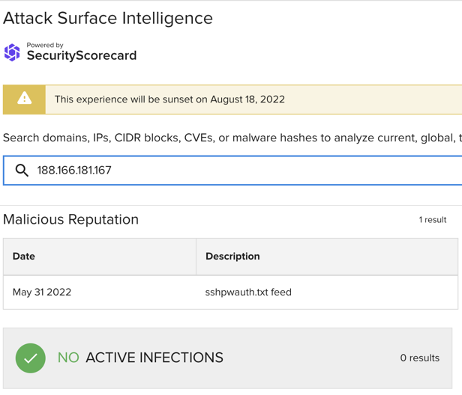

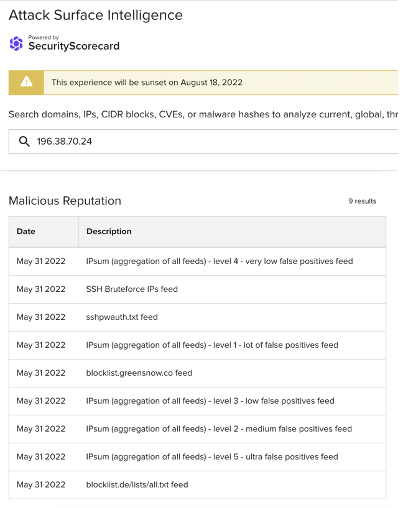

Of the above IP addresses, both ASI’s malicious reputation data (see the representative sample of ASI findings below) and the wider cybersecurity community link the following to SSH brute force attacks:

159.65.240[.]232

188.166.181[.]167

104.248.157[.]240

128.199.251[.]65

165.22.240[.]154

31.220.17[.]31

41.63.9[.]36

159.65.154[.]92

103.4.119[.]20

167.71.131[.]111

68.183.142[.]49

139.59.168[.]22

161.35.127[.]34

165.22.49[.]42

159.223.61[.]129

137.184.215[.]32

128.199.145[.]5

164.92.150[.]6

165.227.167[.]225

167.71.204[.]59

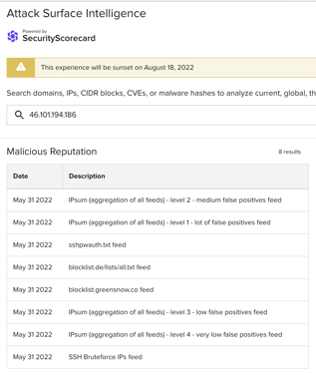

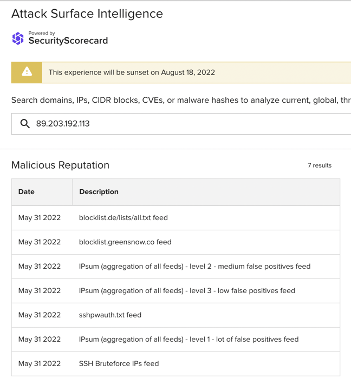

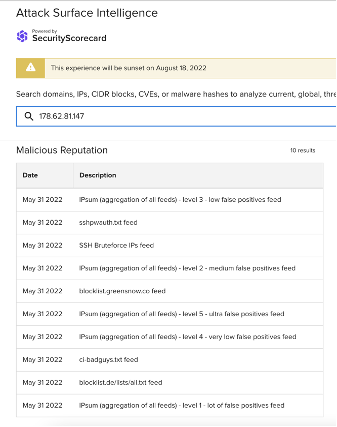

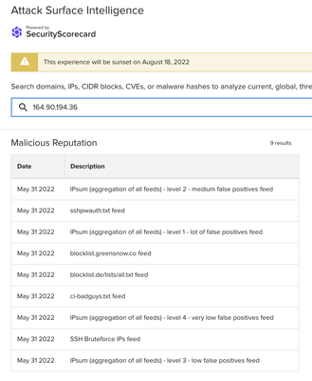

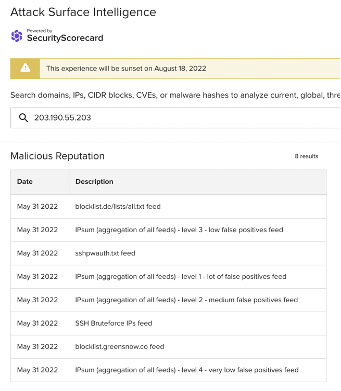

Images 1-3: ASI has linked many of the non-school district IP addresses involved in the traffic observed on June 5 to SSH brute force attacks

While ASI does not have any malicious reputation data on the following IP addresses, other community members have observed them conducting SSH brute force attacks:

June 7

The next possible attack occurred on June 7, when the same three school district IP addresses saw 326 flows using port 22. These involved 24 unique IP addresses, and as with those observed on June 5, other vendors have linked all of them to malicious activity. Those IP addresses are:

198.211.113[.]126

196.38.70[.]24

206.189.205[.]93

103.152.118[.]236

164.92.166[.]153

212.225.176[.]152

64.227.183[.]184

165.22.243[.]115

104.131.34[.]185

142.68.83[.]248

41.94.88[.]60

104.236.49[.]215

206.189.146[.]112

157.230.98[.]148

67.205.130[.]65

104.236.52[.]94

178.62.228[.]214

64.225.16[.]161

157.230.11[.]164

138.68.108[.]37

147.182.139[.]154

164.92.158[.]12

159.203.113[.]193

159.65.203[.]95

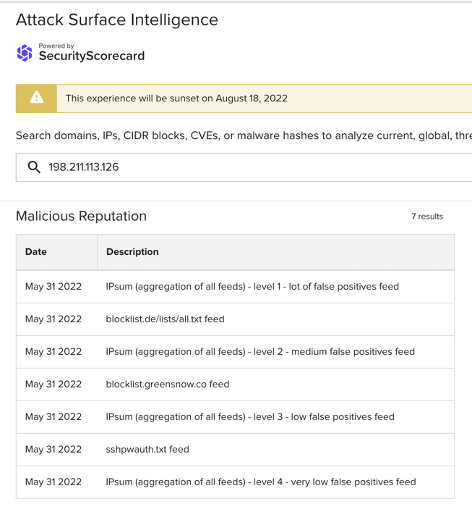

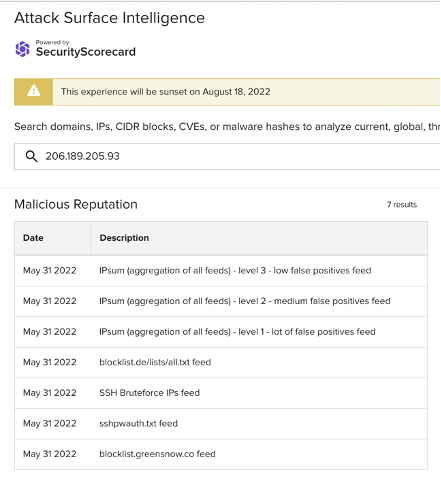

Both ASI’s malicious reputation data (see the representative sample of ASI findings below) and the broader cybersecurity community link all but two of the above IP addresses to SSH attacks. The following are the IP addresses that both data sources have linked to SSH attacks:

198.211.113[.]126

196.38.70[.]24

206.189.205[.]93

103.152.118[.]236

164.92.166[.]153

212.225.176[.]152

64.227.183[.]184

104.131.34[.]185

142.68.83[.]248

41.94.88[.]60

104.236.49[.]215

206.189.146[.]112

157.230.98[.]148

67.205.130[.]65

104.236.52[.]94

64.225.16[.]161

157.230.11[.]164

138.68.108[.]37

147.182.139[.]154

164.92.158[.]12

159.203.113[.]193

159.65.203[.]95

Images 4-6: ASI has linked many of the non-school district IP addresses involved in the traffic observed on June 7 to SSH brute force attacks

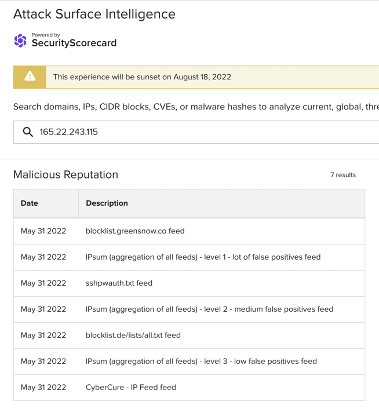

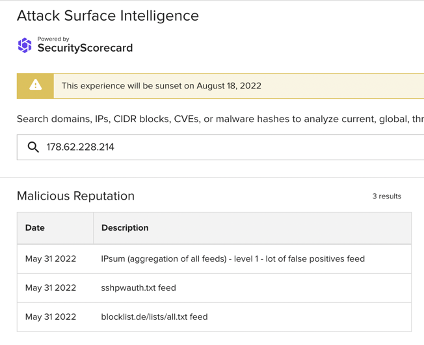

While other vendors’ detections of 165.22.243[.]115 and 178.62.228[.]214 do not specifically name SSH brute force attacks as a concern, ASI’s malicious reputation data has linked them to SSH attacks:

Images 7-8: ASI has linked 165.22.243[.]115 and 178.62.228[.]214 to SSH attacks

June 19

Another possible attack occurred on June 19, when all four school district IP addresses saw 184 flows using port 22. Those flows involved 19 unique IP addresses, one of which, 41.94.88[.]60, also appeared in the June 5 traffic. Vendors have linked all of the other 18 IP addresses to SSH brute force attacks, as has ASI’s malicious reputation data (see the sample of ASI findings below). The IP addresses observed are:

46.101.194[.]186

89.203.192[.]113

104.131.12[.]184

178.62.2[.]24

102.223.92[.]41

165.227.90[.]151

104.248.146[.]6

162.243.28[.]146

128.199.156[.]205

104.248.117[.]154

68.183.188[.]159

178.128.220[.]159

165.227.197[.]236

128.199.90[.]10

178.128.41[.]141

178.128.52[.]254

159.65.25[.]153

68.183.88[.]186

Images 9-11: ASI has linked many of the non-school district IP addresses involved in the traffic observed on June 19 to SSH brute force attacks

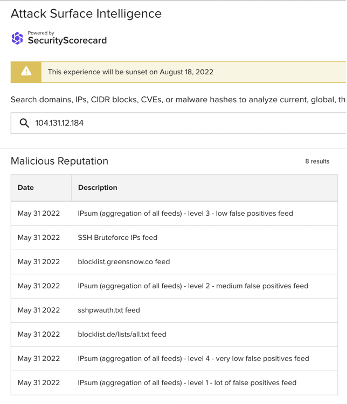

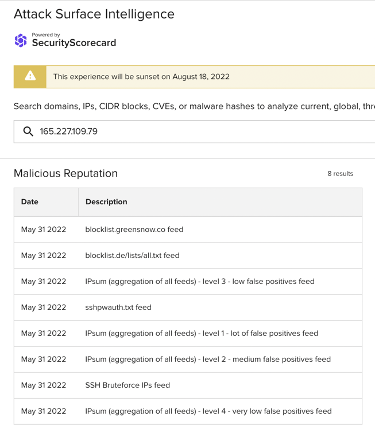

June 10

Another possible attack occurred on June 10, when all four school district IP addresses saw 173 flows using port 22. These flows involved 22 unique IP addresses, two of which, 41.94.88[.]60 and 31.220.17[.]31, appeared in previously-discussed traffic. Vendors have linked all of the other 20 IP addresses to SSH brute force attacks, as has ASI’s malicious reputation data (see the sample of ASI findings below). The IP addresses observed are:

165.227.109[.]79

178.62.81[.]147

164.90.194[.]36

167.99.126[.]215

165.22.69[.]27

162.243.91[.]84

157.245.103[.]207

139.59.31[.]142

103.254.244[.]22

157.245.205[.]66

128.199.250[.]104

46.101.138[.]138

165.232.172[.]31

165.227.54[.]158

139.59.255[.]59

146.190.239[.]5

188.166.91[.]185

188.166.94[.]89

104.236.244[.]98

159.89.170[.]8

Images 12-14: ASI has linked many of the non-school district IP addresses involved in the traffic observed on June 10 to SSH brute force attacks

July 1

Another possible attack occurred on July 1, when all four school district IP addresses saw 163 flows using port 22. These flows involved 17 unique IP addresses, one of which, 41.94.88[.]60, appeared in previously-discussed traffic. Other vendors have linked 15 of the other 16 IP addresses to malicious activity, and ASI has linked the one IP address not detected by other vendors, 104.208.96[.]100, to SSH brute force attacks.

The 14 IP addresses detected by both the wider community and ASI (see the sample ASI results below) are:

203.190.55[.]203

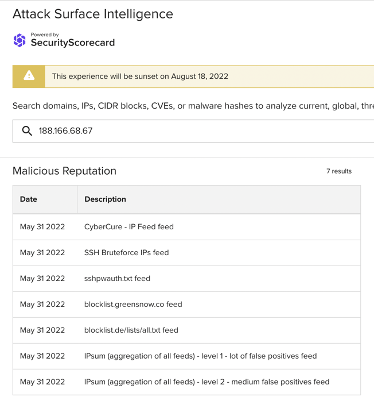

188.166.68[.]67

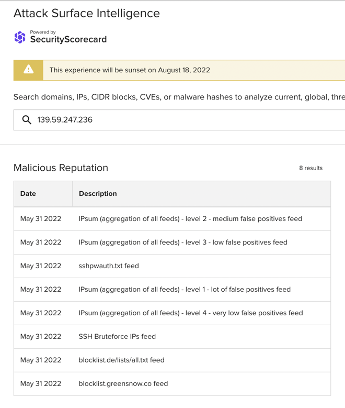

139.59.247[.]236

104.236.31[.]250

41.93.32[.]89

67.205.187[.]133

178.128.97[.]157

170.210.83[.]90

128.199.247[.]226

165.227.227[.]155

128.199.218[.]181

104.131.55[.]236

207.154.241[.]112

222.124.214[.]10

Images 15-17: ASI has linked many of the non-school district IP addresses involved in the traffic observed on July 1 to SSH brute force attacks

While ASI has not linked one IP address, 51.222.12[.]243, to SSH attacks, the wider community has.

Given that either or both the wider cybersecurity community of VirusTotal contributors and SecurityScorecard’s ASI tool have linked all of the IP addresses observed communicating with school district assets over port 22 to SSH attacks, these results suggest this traffic is at least suspicious. It may represent a series of brute force attacks against the school district throughout June and July.

Conclusion

This information was gathered and analyzed to briefly preview some of SecurityScorecard’s Threat Intelligence and investigation capabilities. SecurityScorecard was only able to query and contextualize some of its in-house sources; it, therefore, bears noting that this is not an exhaustive list of issues related to the school district’s overall cyber risk exposure. However, the data researchers have collected and analyzed thus far may offer new insights into the attack and Vice Society’s operations.

The timing of these possible attacks in June and July may suggest that Vice Society attempted credential-stuffing attacks on the school district’s SSH services at an earlier stage in its operation, prior to the presumed encryption of the district’s systems in early August. Such attacks could have employed the exposed passwords contained in SecurityScorecard’s information leak findings or attempted to exploit the high-severity vulnerabilities affecting the SSH software in use at those IP addresses. Since researchers have not previously linked Vice Society to SSH brute force attempts, this traffic may represent a novel dimension of Vice Society’s activity. It is, of course, possible that the suspicious traffic was independent of Vice Society’s attack on the school district. Still, it is not unheard of for ransomware groups to use SSH brute force attacks to access victim systems, even if analysts have not previously observed Vice Society employing such a tactic: 2016 research linked the FairWare ransomware group to such attacks, and Intezer observed ransomware groups employing it in 2019.

How to Prevent Brute Force Attempts in School Districts

To prevent brute force attempts in school districts, schools must have up-to-date cybersecurity procedures that are followed by everyone. Here are some of the best ways to prevent these types of attacks:

Incident Response Support

SecurityScorecard provides managed incident response and digital forensics teams as a professional service driven by a large group of former law enforcement and private sector experts with decades of experience in the space. For immediate support from our teams, please contact us.

Cyber Risk Intelligence as a Service

SecurityScorecard’s threat research and intelligence could be the competitive advantage local governments and educational institutions need to stay ahead of today’s fast-moving threat actors. For more custom insights from our team with 100+ years of combined threat research and investigation experience, or more details on these findings, please contact us to discuss our Cyber Risk Intelligence as a Service (CRIaaS) offering. This investigation should be considered trustworthy but preliminary, and our team can continue diving into these details, especially with the ability to support further by working with on-site staff.

Attack Surface Intelligence

SecurityScorecard’s new Attack Surface Intelligence (ASI) solution gives you direct access to SecurityScorecard’s deep threat intelligence data through a global tab on the ratings platform and via API, all of which were relied upon to conduct this investigation in such a short time frame.

ASI analyzes billions of sources to provide deep threat intelligence and visibility into any IP, network, domain, or vendor’s attack surface risk, from a single pane of glass. This helps a variety of customers do more with the petabytes of data that form the basis of SecurityScorecard Ratings, including identifying all of an organization’s connected assets, exposing unknown threats, conducting investigations at scale, and prioritizing vendor remediation with actionable intelligence.

ASI is built into SecurityScorecard’s ratings platform through an enhanced Portfolio view or Global search across all Internet assets, leaked credentials, and infections and metadata from the largest malware sinkhole in the world. Access ASI today through our Early Access program by filling out the demo request form or by contacting ASI.

Blueprint for Ransomware Defense

On August 4, the Institute for Security and Technology’s (IST) Ransomware Task Force (RTF) announced the release of its Blueprint for Ransomware Defense – a clear, actionable framework for ransomware mitigation, response, and recovery aimed at helping organizations navigate the growing frequency of attacks.

SecurityScorecard is proud to be the only security ratings platform to sponsor and participate in the development of The Blueprint, and is one of only 5 organizations who participated in the program’s development.

You can see the Blueprint for Ransomware Defense here.