The Increase in Ransomware Attacks on Local Governments

Executive Summary of Local Government Ransomware Attacks

- SecurityScorecard’s threat research team undertook a broad survey of recent developments in ransomware activity affecting the state and local government and education (SLED) sectors.

- The ALPHV/BlackCat and LockBit 2.0 ransomware groups appear to have been responsible for a notable portion of activity targeting SLED organizations in 2022.

- Ransomware groups have continued to modify their TTPs throughout 2022; although their main points of entry (phishing, compromised remote access services, and exploitation of known vulnerabilities) have remained broadly consistent, their specific methods have evolved; SecurityScorecard observed ransomware groups exploiting new Apache and Confluence vulnerabilities in Q2 2022 attacks.

- Third-party risks have also persisted, with ransomware attacks against SLED institutions’ vendors leading to client data breaches.

- SecurityScorecard can support SLED organizations both before and after ransomware attacks:

- SecurityScorecard’s security rating platform gives organizations an outside-in view of their existing cybersecurity posture to take action against inherent vulnerabilities and risks. In addition, our Attack Surface Intelligence (ASI) and Automated Vendor Detection (AVD) products can enable continuous monitoring of their and their vendor’s digital assets.

- Our Cyber Risk Intelligence as a Service (CRIaaS) offering can provide tailored insights about the threats facing them.

- In the event of a successful or attempted attack, SecurityScorecard’s professional services unit can support incident response efforts.

Introduction

In Spring 2022, Lincoln College announced that it would permanently close on May 13 and noted that a December 2021 ransomware attack had contributed to its closure. Unfortunately, at the same time that Lincoln College was struggling in vain to remain open, other SLED (state, local and educational) institutions were suffering new ransomware attacks, despite years of consistent evidence of ransomware groups’ particularly heavy targeting of those sectors. On March 30, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) issued a private industry notification (PIN) warning of the continued targeting of local governments by ransomware operators, noting that local Government Facilities Sector (GFS) entities were the second-most frequent victims to report ransomware incidents to the FBI in 2021. The notification goes on to highlight four incidents that affected county governments and identifies phishing, remote desktop protocol (RDP) compromise, and exploitation of unpatched vulnerabilities as the three most common means by which threat actors initially accessed victims’ systems. In another relevant PIN, the FBI noted in May 2022 that members of illicit forums regularly sell educational institutions’ credentials. Exposed credentials may in fact be both a cause and effect of some attacks. Not only do ransomware groups often use previously exposed credentials to access victim networks but, as the PIN notes, some attackers also use an intrusion that ultimately results in a ransomware deployment to harvest credentials from victim organizations.

In a summary study of 2021 ransomware incidents, Sophos surveyed a group of 499 information technology professionals in the education sector. They found that 44% of respondents’ organizations had experienced ransomware attacks that year. Of those attacks, 58% resulted in the successful encryption of data, and 35% of successful encryptions led to ransom payments. Moreover, Sophos’ statistics suggest that educational institutions may be less capable of detecting attacks than other targets. The percentage of attacks resulting in encryption for targets in education (58%) was 4% higher than the overall average (54%.) In comparison, the percentage of respondents reporting that attacks were stopped before encryption was 2% lower in education than overall (37% vs. 39%) and the percentage that paid ransoms was 3% higher (35% vs. 32%).

Sophos also surveyed local government personnel in its study, finding that local governments were the organizations least capable of disrupting attacks prior to encryption: 69% of respondents from local governments that suffered attacks reported those attacks led to the encryption of their organizations’ data. Moreover, local governments were among the ransomware victims to pay ransoms most frequently: 43% of local government respondents reported that their organizations had paid a ransom after an incident.

Meanwhile, Emsisoft’s retrospective report on 2021 ransomware incidents found that ransomware attacks had affected 77 state and local governments and 1,043 schools that year, leading to an estimated minimum of 36 data breaches in local government and 118 in education. This may indicate decreased targeting of local government, as 2021’s 77 victim organizations is considerably fewer than the 113 recorded in both 2019 and 2020. Emsisoft additionally notes that smaller municipalities also made up a larger proportion of 2021 victims, in contrast to previous years, whose ransomware victims included large cities like Atlanta and Baltimore.

Unlike local government, according to Emsisoft’s research, the number of victims in the education sector did not decrease notably in 2021. 2020 saw 84 attacks against 26 colleges or universities and 58 school districts (impacting 1,681 individual schools within those districts). In 2021, 88 incidents occurred, and the number of higher-education victims remained 26, while the number of school districts increased to 62. However, the number of schools affected by attacks against those districts decreased to 1043. This suggests that ransomware groups are targeting smaller educational organizations more often, just as they appear to have begun targeting smaller municipalities.

While 2022 is not over yet (and full-year statistics are therefore not yet available), early indications are that ransomware attacks against targets in both local government and education will persist, if not increase. In early April, Recorded Future reported that 37 schools had suffered ransomware attacks in the first quarter of 2022 alone, compared to 127 in all of 2021. This included seven confirmed victims in higher education:

- North Carolina A&T University

- Ohlone College

- Savannah State University

- University of Detroit Mercy

- Centralia College

- Phillips Community College of the University of Arkansas

- National University College (NUC University)

In response to a later attack, another expert reported at the end of April that ransomware had affected 12 institutions of higher education up to that point in the year, with 10 of those incidents involving data theft, additionally noting that 9 school districts comprised of 234 individual schools had suffered attacks up to that point in 2022. Like the estimates above, these figures would suggest that more attacks on the education sector will occur in 2022 than 2021, were they to continue at the same rate. Unlike education, however, attacks against local governments may be decreasing. According to one estimate, as of early June, 22 local governments had suffered attacks, but by the same point in 2021, 36 local government attacks had occurred.

Particularly Active Groups: ALPHV/BlackCat and LockBit 2.0

Of the year’s publicly-disclosed ransomware attacks against higher education and local government, the LockBit 2.0 and ALPHV/BlackCat groups have figured particularly prominently. Of the above reports, ALPHV claimed responsibility for the attacks on North Carolina A&T and Phillips Community College, while LockBit 2.0 claimed the University of Detroit Mercy and NUC University attacks. ALPHV subsequently claimed additional attacks on Florida International University and Regina Public Schools and LockBit 2.0 claimed an attack against Mercyhurst University (though shortly after claiming the attack, LockBit removed Mercyhurst’s entry from its leak site). Most recently, on June 3, 2022, the town of Alexandria, Louisiana reported that it had suffered a breach resulting from an attack by ALPHV. Commentators have noted that the group took a particularly aggressive stance against media coverage in addition to making more predictable threats to leak data directed at state officials.

ALPHV (also tracked as BlackCat) and LockBit 2.0 are both ransomware-as-a-service (RaaS) operations that reportedly conduct double and, in some cases, triple extortion against their victims: in addition to demanding a ransom to decrypt encrypted systems, they not only threaten to publish stolen data on their leak sites, but also occasionally launch distributed denial of service (DDoS) attacks against their victims to apply additional pressure by way of additional disruptions to their operations and recovery efforts. Both groups also often employ Cobalt Strike in the course of their attacks.

As its name suggests, LockBit 2.0 is a continuation of the earlier LockBit ransomware operation, which first surfaced in 2019 (LockBit 2.0 appeared in Summer 2021). According to an FBI advisory released in February 2022, LockBit 2.0’s affiliates have accessed target systems by a variety of means, including remote access purchased through initial access brokers, exploitation of vulnerabilities both novel and published, and through malicious insiders. More recent analysis of the group found that LockBit 2.0’s operators have sought affiliates who can help compromise target systems through phishing, remote services including RDP and VPN, previously exposed credentials, and insider access.

ALPHV first appeared in early December 2021. Early analysis found the BlackCat strain of ransomware to be particularly sophisticated and that it was the first professionally-deployed ransomware to be written in Rust. Later, in April 2022, the FBI warned that as of March, ALPHV/BlackCat had already compromised 60 organizations and noted that the operation likely shared personnel with the BlackMatter and DarkSide groups. DarkSide achieved considerable notoriety for its attack on Colonial Pipeline, which likely led the group to rebrand, first as BlackMatter and later as BlackCat. That warning notes that attackers normally exploit previously exposed credentials to access victim systems, subsequently escalating privileges and moving laterally while disabling security systems to avoid detection. As with many other ransomware operations, the group steals documents from victim systems in order to conduct secondary extortion and uses Cobalt Strike after initially compromising victim systems. More recent research has found that some BlackCat affiliates have exploited a Microsoft Exchange vulnerability to initially access unpatched servers–although the research does not explicitly name the Exchange vulnerability in question, it may be the widespread ProxyLogon vulnerability that was first disclosed in early 2021, given that researchers link to guidance about it in the newer report.

Ongoing Risks of Local Government: Third-Party/Supply Chain Breaches

Third-party risk has been a recurring topic of concern within the cybersecurity community, and third-party breaches have proven particularly relevant in discussions of the impact of ransomware upon government and educational institutions. In addition to direct attacks against them, ransomware attacks against other businesses have also led to breaches of government and educational institutions’ data.

In July 2020, Blackbaud, a technology provider that caters to nonprofit organizations, notified customers (including many K-12 schools, colleges, and universities) that a February ransomware attack had also exposed their data, but that Blackbaud had paid the ransom, partially in hopes of preventing the attackers’ publication of the stolen data.

The Accellion FTA compromise that became prominent in early 2021 is a particularly wide-ranging example of the intersection between supply-chain cyber risk and ransomware. Between December 2020 and January 2021, Accellion patched a group of vulnerabilities in its 20-year-old FTA file transfer software. However, by that point, threat actors had already exploited them to steal data from Accellion customers and partners and subsequently began contacting those customers and partners to threaten to leak the stolen data and demand a ransom; by February 2021, victim data had begun appearing on the Cl0p ransomware group’s leak site. Analysts estimated at the time that the attacks affected 100 organizations, 25 of which experienced severe data thefts. Educational institutions, including Stanford University, the University of California system, the University of Colorado, the University of Miami, the University of Maryland, Baltimore, and at least one state government were among the affected organizations.

Thus far, breaches at two different educational technology (edtech) providers, Illuminate Education and Battelle for Kids, have affected public school districts’ data in 2022; at least one of these (Battelle) was the result of a ransomware attack. Illuminate Education announced in January that service disruptions reported by customers, including the New York City public school system, were the result of an unspecified security incident. Then, in March, Illuminate informed New York City officials that the incident had also led to a data breach that exposed 820,000 New York City students’ personal data. Some features of this incident resemble a ransomware attack, but public sources have not yet formally identified it as one. In a similar event publicly acknowledged as a ransomware incident, in April, a group of Ohio school districts began announcing breaches resulting from a December 2021 attack against edtech provider Battelle for Kids, with the much larger Chicago public school system announcing in May that the Battelle attack had also impacted it, leading to a breach of 500,000 students’ and 60,000 teachers’ data.

Even in the wake of their respective security incidents, SecurityScorecard’s platform indicates that Battelle and Illuminate both suffer from issues attackers (including ransomware operators) could exploit. Previous leaks have exposed personal information belonging to employees of both organizations, and other leaks have exposed passwords associated with Battelle email addresses. An attacker could use exposed personal information to craft compelling phishing messages, and ransomware attacks have often used employee credentials (like passwords that employees use across different accounts and fail to change after their exposure in a breach) to access target systems. Both could be susceptible to phishing attacks: 17 domains attributed to Battelle for Kids lack Sender Policy Framework (SPF) records, and the SPF record for one Illuminate Education subsidiary, IO Education, indicates a misconfiguration. SPF can help prevent email spoofing, but in its absence, threat actors can more easily craft and distribute phishing emails that can be more convincing because they appear to have originated from within a target organization. SecurityScorecard also observed open FTP services at an IP address attributed to Battelle as recently as June 17. Speaking generally, attackers may take an interest in file-sharing services because they offer a means of accessing victim data, but some ransomware groups have taken a particular interest in it. For example, Sophos warned in February 2021 that it had observed the Conti group using FTP to steal victim data. Software in use on June 20 and 21 at Illuminate-attributed IP addresses also appeared to be affected by high-severity vulnerabilities first identified in 2016 and 2018, which could indicate patch management issues that could be especially concerning given that ransomware often exploits unpatched vulnerabilities. Other issues, while not necessarily targeted by ransomware groups, may nonetheless indicate an ongoing risk.

SecurityScorecard has previously researched the links between our scorecard factors and ransomware attacks to identify which of the issues we observe are more prevalent among ransomware victims than in other organizations. Many of the issue types identified in this research also affect Battelle for Kids and Illuminate Education. Exposed personal information (observed for both companies, as discussed above) was almost 40% more prevalent among the ransomware cohort than non-victim organizations. SecurityScorecard observed TLS services that support weak protocols in use in Battelle’s and Illuminate’s networks; this finding is over 30% more prevalent among ransomware victims than non-victims. SecurityScorecard’s earlier research also noted that two other TLS flaws, TLS Service Supports Weak Cipher Suite, and Certificate Without Revocation Control, are respectively 30% and 29% more prevalent in the ransomware cohort than in the control group. SecurityScorecard has found a TLS Service at a Battelle for Kids-attributed IP address to support a weak cipher suite and a TLS certificate at an Illuminate Education-linked IP address to lack revocation control. Together, these findings suggest that both Battelle for Kids and Illuminate Education may share a profile similar to many ransomware victims, even if only one of the two companies has publicly disclosed a ransomware incident in recent months.

Local Government Ransomware Attack Case Studies

Alexandria, Louisiana

SecurityScorecard’s investigation into the attack against the government of Alexandria, Louisiana, by the ALPHV group revealed some possible insights, including a series of suspicious network flows (netflows) in the days before the attack.

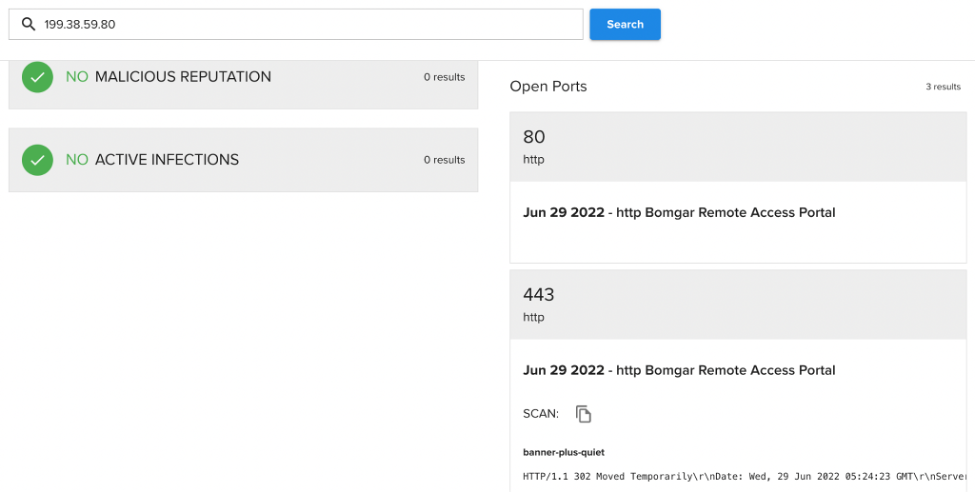

On May 30 and 31, 151 flows between 199.38.59[.]80 (an IP address attributed to the City of Alexandria) and 149.255.169[.]10 took place over UDP. These occurred within fairly narrow timeframes: the 25 flows on May 30 occurred between 16:26:25 and 16:28:54 UTC, and the 126 flows on May 31 all occurred between 11:22:14 and 11:42:12 UTC. SecurityScorecard’s netflow tool has previously linked 149.255.169[.]10 to malicious bot and Cobalt Strike activity. ASI has, moreover, revealed remote access services in use at open ports at the Alexandria IP address in question:

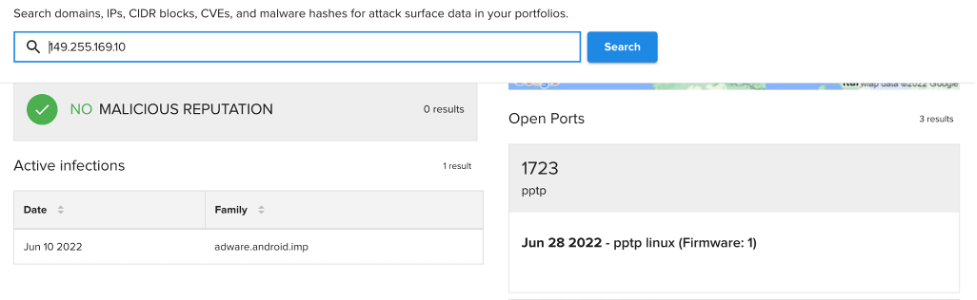

ASI also found a port indicative of VPN activity open at the other IP address involved in these flows; Point-to-Point Tunneling Protocol (PPTP) is a VPN protocol that operates on TCP port 1723, a port that ASI indicates is open at 149.255.169[.]10. While PPTP is widely regarded as outdated, VPNs can also use UDP (the protocol over which the observed communication occurred) in its stead.

While VPNs do not necessarily indicate malicious activity, threat actors use them regularly to obfuscate their traffic and communications.

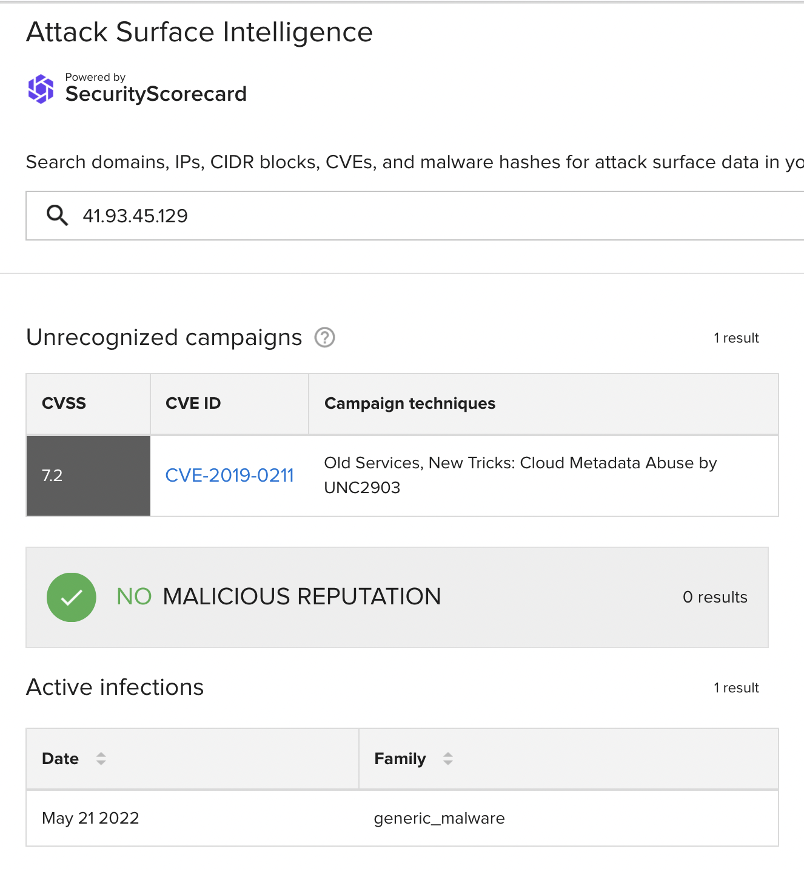

These 151 flows make up the bulk of the observed traffic involving this particular Alexandria-attributed IP (199.38.59[.]80), which comprised 186 flows in total and may represent a particularly concentrated period within a broader pattern of suspicious activity. The first flow within SecurityScorecard’s sample took place between 199.38.59[.]80 and 41.93.45[.]129 on May 21. Other vendors have observed this IP address leading to a download of a malicious javascript file, and ASI observed a malware infection active there on the same day as this flow:

The malicious file in question has, moreover, figured in previous SecurityScorecard research, which linked it to possible Russian C2 infrastructure. The number of bytes observed in this flow (1500, or 15 KB) is only slightly larger than the javascript file in question (10.66 KB).

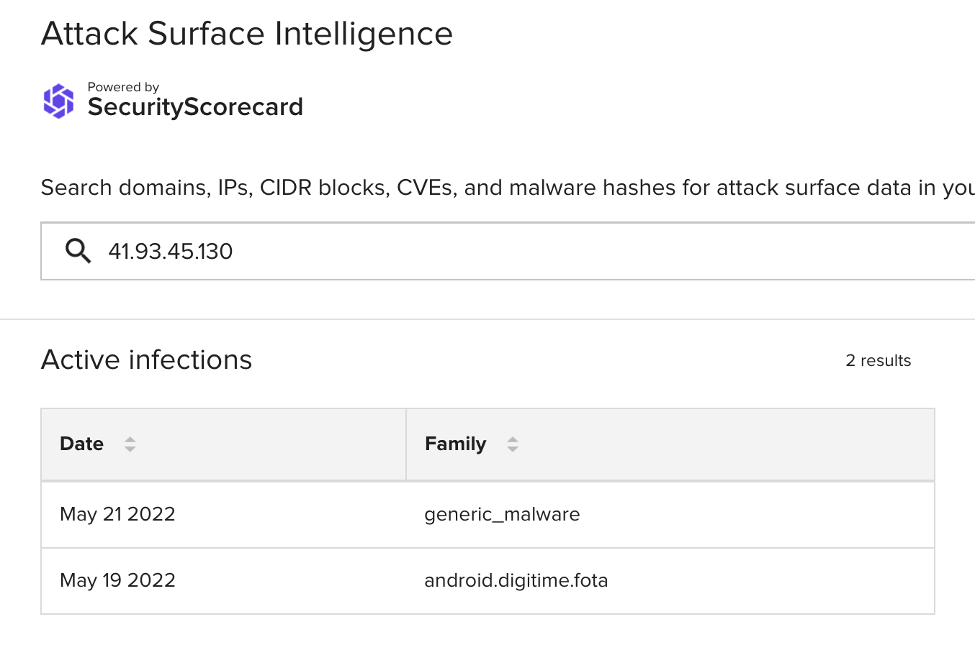

The following day (May 22), the same Alexandria IP address communicated with a neighboring IP address, 41.93.45[.]130. Vendors have linked that address to malicious activity and ASI observed malware infections at it only slightly before this flow:

Then, on May 23, a 327-KB data transfer from 178.128.55[.]198 took place. Nine vendors have detected malicious activity involving this IP address; it has hosted a domain that appears to impersonate Apple (icdn-appieid[.]com) and, more recently, was observed leading to a download of a malicious text file detected as Win32.Trojan.Raasj.Auto.

These three flows used TCP, but after them, many others, like the 151 involving 149.255.169[.]10, used UDP. This sudden shift to UDP may reflect the use of a VPN to communicate with threat actor infrastructure following an initial compromise represented by these first three suspicious TCP flows.

While this traffic may be benign (internal log data could further elucidate it), these findings suggest that the above-discussed IP addresses merit further investigation, as the timing of the traffic involving them suggests that they may have played a role in the attack against the Alexandria government.

Somerset County, New Jersey

On May 24, the government of Somerset County, New Jersey, announced it had suffered a ransomware attack earlier that day, which disabled the county’s email system and disrupted Somerset County Clerk and Surrogate services requiring internet connectivity or access to county databases. Following the disclosure of the incident, SecurityScorecard researchers consulted our internal scan data and netflow tool in hopes of enriching the publicly available information about the attack. SecurityScorecard observed several vulnerabilities commonly leveraged by ransomware groups on Somerset County’s network.

SecurityScorecard observed that Somerset County’s main domain, somerset[.]nj[.]us, lacked an SPF (sender policy framework) record as recently as May 23. SPF can help prevent email spoofing by verifying that emails claiming to originate from a given domain are coming from a server with a legitimate relationship to that domain, thus reducing the risk of successful phishing attacks. A threat actor could, for example, have begun spoofed emails from somerset[.]nj[.]us to phish Somerset County employees at the beginning of the ransomware attack against the county. As SecurityScorecard’s recent cases have also revealed, phishing remains a common means of initial access for ransomware. With that said, recent years have also seen ransomware groups use a remote desktop protocol to access victim systems with increasing frequency.

SecurityScorecard additionally observed FTP services publicly available at three Somerset County-attributed IP addresses, 64.206.95[.]16, 64.206.95[.]15, and 64.206.95[.]23. As discussed above, researchers have observed ransomware groups and other threat actors exploiting FTP in the past.

As seen above, exploitation of known vulnerabilities also remains a common feature of ransomware attacks, and SecurityScorecard observed a number of CVEs affecting Somerset County IP addresses. Five of these, in particular, 64.206.95[.]22, 64.206.95[.]27, 64.206.95[.]24, 64.206.77[.]196, and 64.206.95[.]21 may suffer from one especially prominent and relatively recent vulnerability, Spring4Shell, the exploitation of which, some commentators note, could facilitate the deployment of ransomware.

SecurityScorecard’s netflow data revealed a notable amount of traffic that may indicate attackers’ use of Cobalt Strike against Somerset County. From April 24 to May 24 (the month leading up to the Somerset County government’s detection of the attack), the netflow data available to SecurityScorecard revealed 41,972 flows between the IP addresses attributed to Somerset County and IP addresses linked to Cobalt Strike command-and-control infrastructure. Some of this traffic may have been part of the attack reported on May 24. According to Cisco research conducted in 2020, 66% of ransomware attacks observed that year used Cobalt Strike. More recently, in February 2022, Cybereason’s Global SOC Team analyzed an attack they attribute to a Conti ransomware affiliate that began with spear phishing directed at employees of the victim organization and later deployed Cobalt Strike. Given the SPF issue mentioned above, it is not unthinkable that the attack against Somerset County followed a similar trajectory.

To identify the most concerning IP addresses involved in the almost 42,000 flows that could reflect the use of Cobalt Strike against Somerset County, SecurityScorecard researchers first limited the results to those involving Somerset County IP addresses where SecurityScorecard’s platform observed issues, as these issues could represent vulnerabilities that adversary may be more likely to target. They then sorted the results by byte count in order to identify the Cobalt Strike-tagged IP addresses involved in the largest data transfers. The top 10 IP addresses linked to Cobalt Strike and involved in large data transfers to or from Somerset County are the following (in order of byte count):

- 165.225.242[.]248

- 208.87.239[.]180

- 208.40.200[.]194

- 192.216.142[.]51

- 162.142.125[.]211

- 174.128.243[.]54

- 154.89.5[.]80

- 70.39.102[.]189

- 128.14.133[.]58

- 174.128.243[.]54

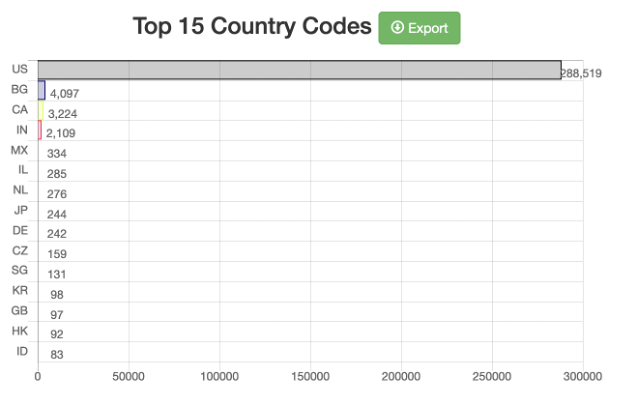

Researchers then identified additional traffic involving other IP addresses located in the same countries as these known malicious IPs when the countries in question are ones with which a US local government would be unlikely to communicate. This led SecurityScorecard to observe large data transfers between vulnerable Somerset assets and IP addresses in India and Bangladesh in the weeks leading up to the attack. Researchers observed a total of 2,109 flows between the county government’s assets and Indian IP addresses. Traffic between Indian IP addresses and those attributed to the Somerset County government is in and of itself something of an anomaly: the vast majority of traffic occurred within the US, as reflected in the graph below:

Despite the low frequency of the traffic, the volume of the data it transferred was quite large: flows involving Indian IP addresses had an average byte count of 3,363,767, more than double the overall average (1,576,056 bytes). Because traffic between Somerset County IPs and Indian IPs appears uncommon, the amount of data transferred in that traffic was anomalously large. The transfers occurred in the lead-up to a ransomware deployment, and threat actors have been observed abusing Indian infrastructure in previous attacks. Of the IP addresses appearing in the attack, 103.240.208[.]197 may represent a particular cause for concern. SecurityScorecard’s netflow tool has associated it with Cobalt Strike, and researchers detected a transfer of 156,000 bytes between it and one vulnerable Somerset County IP address, 64.206.95[.]4, on May 24, the date Somerset County detected and disclosed the attack against it.

In contrast to those located in India, the Bangladeshi IP addresses communicating with Somerset County assets were both rarer and transferred smaller amounts of data. Between April and May 24, they only appeared in 40 flows and had an average byte count of 506,863. However, in addition to the links SecurityScorecard’s netflow tool established between some of these IPs and malicious bot activity, the heavy concentration of the traffic on certain specific dates appears somewhat suspicious. Of these 40 flows, 18 occurred on May 8 and involved larger data transfers than the overall average of 506,863; on May 8, the flows’ average byte count was 1,113,500. Although the IP involved, 103.92.85[.]202, has not previously been linked to ransomware, it likely merits investigation, if not blocking, because traffic between Somerset County IPs and Bangladeshi IPs appears uncommon. The amount of data transferred in that traffic was anomalously large and the transfers occurred in the lead-up to a ransomware deployment. Moreover, other members of the cybersecurity community have previously linked it to brute force attacks targeting RDP. Ransomware groups often compromise RDP for initial access.

Traffic on another day, May 12, represented the next-largest portion of the flows observed: 14 occurred on that day. They all involved one Bangladeshi IP, 37.111.205[.]165, which another vendor has linked to Cobalt Strike. Their average byte count (6,957.5 bytes), however, was considerably smaller than the one observed on May 8.

Findings from Ransomware Attacks on Local Government

Recent incident response efforts in which SecurityScorecard was involved do, in general, indicate that ransomware groups’ TTPs have remained largely continuous with those employed in 2021, with the exploitation of known vulnerabilities remaining a consistent feature of recent attacks. However, the vulnerabilities exploited have changed as researchers publish new CVEs.

Thus far in 2022, Confluence, GitHub, and Apache vulnerabilities have figured particularly prominently in SecurityScorecard cases. Since its publication in February, CVE-2021-44228 (an Apache vulnerability also tracked as “Log4Shell” because it affects Apache’s Log4j software library) has figured in approximately six incidents to which SecurityScorecard responded. More recently published research may also reflect the exploitation of Confluence vulnerabilities observed by SecurityScorecard. Analysts first reported that they had observed the Cerber ransomware group exploiting CVE-2021-26084. This vulnerability permits attackers to execute arbitrary code on affected versions of Atlassian’s Confluence Server and Data Center products in December 2021. Atlassian later advised Confluence users that a new remote code execution vulnerability, CVE-2022-26134, was under active exploitation on June 2. By June 11, researchers had observed at least two ransomware groups (including the aforementioned Cerber) exploiting it. In one particularly glaring incident, SecurityScorecard observed 64 open CVEs, including both Log4Shell and a GitHub vulnerability on a client’s system.

Despite targeting newer vulnerabilities, systems that remain unpatched long after the publication of a CVE will also remain low-hanging fruit for attackers. In one recent engagement with a municipal emergency response service, SecurityScorecard determined that a threat actor had originally accessed the target’s network through its VPN, exploiting a vulnerability in its firewall, which the victim organization had not updated in over a year. In this particular case, the adversary remained in the victim’s network for months and loaded, but ultimately did not deploy ransomware on its systems. The decision not to encrypt this organization’s devices, and particularly the time it took for the threat actors to reach that decision, may reflect a wider trend.

Despite these general continuities with previously established trends, recent cases have also revealed two novel features of ransomware operations in 2022: increasing dwell time and aggression. In the municipal emergency service incident, SecurityScorecard determined that the attacker spent 90 days in the victim system prior to detection. According to SecurityScorecard experts, this reflects a broader trend: threat actors are taking their time more. Threat actors often do not know what data they are stealing during exfiltration, but if they have gone undetected, they increasingly appear to be willing to spend the time to figure out what data they can access and what it is worth. In previous cases, SecurityScorecard was able to determine that attackers viewed some data but did not exfiltrate it, likely because they believed that they could not monetize it, a belief likely shaped by time constraints–they were unwilling or unable to spend the time to study victim data and make an informed assessment of its value. However, longer dwell times may suggest that actors hope to make more informed decisions about what data they can monetize.

More than just seeking to evaluate the data available to them, in the municipal emergency response case, the adversaries disabled the victim’s anti-virus software to avoid detection. They then spent some of their 90-day dwell time attempting further vertical and lateral movement, perhaps in hopes of breaching more lucrative targets. From the emergency service, for example, attackers tried to access the internal systems of other local government bodies, including city hall, and launched DNS poisoning attacks from the infected system.

SecurityScorecard has also observed ransomware groups taking increasingly aggressive steps to pressure their victims to pay ransom. In addition to the secondary and tertiary extortion methods mentioned above, attackers have taken more personal steps in recent incidents, contacting friends and family members of executives of some affected organizations to exert additional pressure.

Conclusion: How to Prevent Ransomware Attacks on Local Governments

Although some statistics suggest that the targeting of educational institutions by ransomware operators has decreased in 2022, their targeting of local governments may have increased. SecurityScorecard’s findings suggest that a number of issues affecting organizations in these sectors could render them particularly vulnerable to ransomware. To reduce their vulnerability, organizations should make every effort to keep software up to date; unpatched software is easier to exploit. In addition to those appearing on previously-circulated lists of CVEs frequently exploited by ransomware, those observed in recent SecurityScorecard engagements may merit particular attention. They should also remain on guard against phishing: frequent training would complement the use of SPF, DKIM, and DMARC, which can reduce the risk of email spoofing. While some credential exposures may be unavoidable, organizations can also reduce the risks associated with these exposures by advising employees against password reuse, requiring 2FA, and requiring fairly stringent length and complexity requirements for passwords. While SecurityScorecard gathered and analyzed this information to provide an overview of some of SecurityScorecard’s threat intelligence and investigation capabilities as they relate to SLED organizations’ exposure to ransomware, the discussion above may not serve as an exhaustive enumeration of every possible threat and risk involving ransomware. However, SecurityScorecard can offer more tailored support for SLED organizations both before and after ransomware attacks.

How to Prevent Ransomware Attacks on Local Governments

To prevent ransomware attacks on local governments, these institutions must have up-to-date cybersecurity procedures that are followed by everyone. Here are some of the best ways to address and prevent these types of attacks:

Incident Response Support

In the event of a confirmed or suspected ransomware attack, SecurityScorecard can provide managed incident response and digital forensics teams as a professional service to customers driven by a large group of former law enforcement and private sector experts with decades of experience in the space. For immediate support from our teams, please contact Ranell Gonzales.

Cyber Risk Intelligence as a Service

SecurityScorecard’s threat research and intelligence could be the competitive advantage SLED organizations need to stay ahead of today’s fast-moving threat actors. For regular custom insights through our team’s 100+ years of combined threat research and investigation experience, or more details on these findings and the other keywords that were provided, please contact Ranell Gonzales for a discussion of our Cyber Risk Intelligence as a Service (CRIaaS) offering. While this report should be considered trustworthy but preliminary, our team can continue diving into these details and offer further support by working with on-site staff at local government and educational institutions. We can, for example, conduct additional analysis on the malware, targets, data transfer destinations, and specific context around the leaked credentials at a given organization.

Attack Surface Intelligence

SecurityScorecard’s new Attack Surface Intelligence (ASI) solution gives you direct access to SecurityScorecard’s deep threat intelligence data through a global tab on the ratings platform.

ASI analyzes billions of sources to provide deep threat intelligence and visibility into any IP address, network, domain, or vendor’s attack surface risk, from a single pane of glass. This helps customers do more with the petabytes of data that forms the basis of SecurityScorecard Ratings, including identifying all of an organization’s connected assets, exposing unknown threats, conducting investigations at scale, and prioritizing vendor remediation with actionable intelligence.

ASI is built into SecurityScorcard’s ratings platform through an enhanced Portfolio view or global search across all Internet assets, leaked credentials, and infections and metadata from the largest malware sinkhole in the world. Access ASI today through our Early Access program by filling out the demo request form or contacting Assel Dmitriyeva.

Blueprint for Ransomware Defense

On August 4, the Institute for Security and Technology’s (IST) Ransomware Task Force (RTF) announced the release of its Blueprint for Ransomware Defense – a clear, actionable framework for ransomware mitigation, response, and recovery aimed at helping organizations navigate the growing frequency of attacks.

SecurityScorecard is proud to be the only security ratings platform to sponsor and participate in the development of the Blueprint and is one of only 5 organizations who participated in the program’s development.

You can see the Blueprint for Ransomware Defense here.