Investigations of Lazarus Group Indicators of Compromise Reveals Suspicious Traffic Involving State Government IP Addresses

Executive Summary

- In early February, analysts attributed a new intrusion affecting a healthcare research organization to the Lazarus Group, a well-established threat actor believed to act on behalf of the government of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK).

- In an effort to enrich the Indicators of Compromise (IoCs) provided in the original report, the SecurityScorecard Threat Research, Intelligence, Knowledge, and Engagement (STRIKE) Team consulted internal and external data sources for additional data regarding the IP addresses listed in it.

- During their investigation, STRIKE Team researchers observed traffic that may indicate targeting of a state government’s oil and gas board.

- While this traffic may not represent Lazarus Group activity, it likely merits further attention as it may still represent an attempt to access government systems by other threat actors.

- Other traffic may offer some insights into the behavior associated with the IP addresses in question, if not with a specific threat actor group.

Background

In early February, analysts attributed a new intrusion affecting a healthcare research organization to the Lazarus Group, a well-established threat actor believed to act on behalf of the government of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK). While investigating this intrusion, these analysts linked it to a wider campaign targeting organizations in other sectors, including manufacturing, higher education, and research. It may also be notable that the affected manufacturing firm produces technology used in other critical sectors such as energy, research, defense, and healthcare. Organizations in these fields could, therefore, also be targets of similar activity.

The report provided ten IP addresses in its list of IoCs. To enrich the IoCs provided in the original report, STRIKE Team researchers consulted internal and external data sources for additional data regarding these IP addresses.

Methodology

Researchers first used SecurityScorecard’s exclusive access to network flow (NetFlow) data to collect a sample of traffic involving the IP addresses named as Lazarus Group IoCs in the report. To identify possible targets of the campaign, researchers searched for the IP addresses appearing in this sample in public sources of ownership data to determine the organizations that own the IP addresses with which the Lazarus Group-linked IP addresses communicated.

In the case of IP addresses belonging to service providers other organizations may use, researchers queried SecurityScorecard’s Attack Surface Intelligence tool to identify the organizations to which SecurityScorecard has attributed the IP addresses, as those organizations are also possible targets of the activity.

Findings

Throughout the two-month observation period, 28,185 unique IP addresses communicated with the ten IP addresses appearing in the alert. Most of these belonged to search engines, hosting providers, and telecommunications companies. Therefore, the traffic involving them was either likely irrelevant to the activity discussed in the report or unlikely to offer additional insights regarding it.

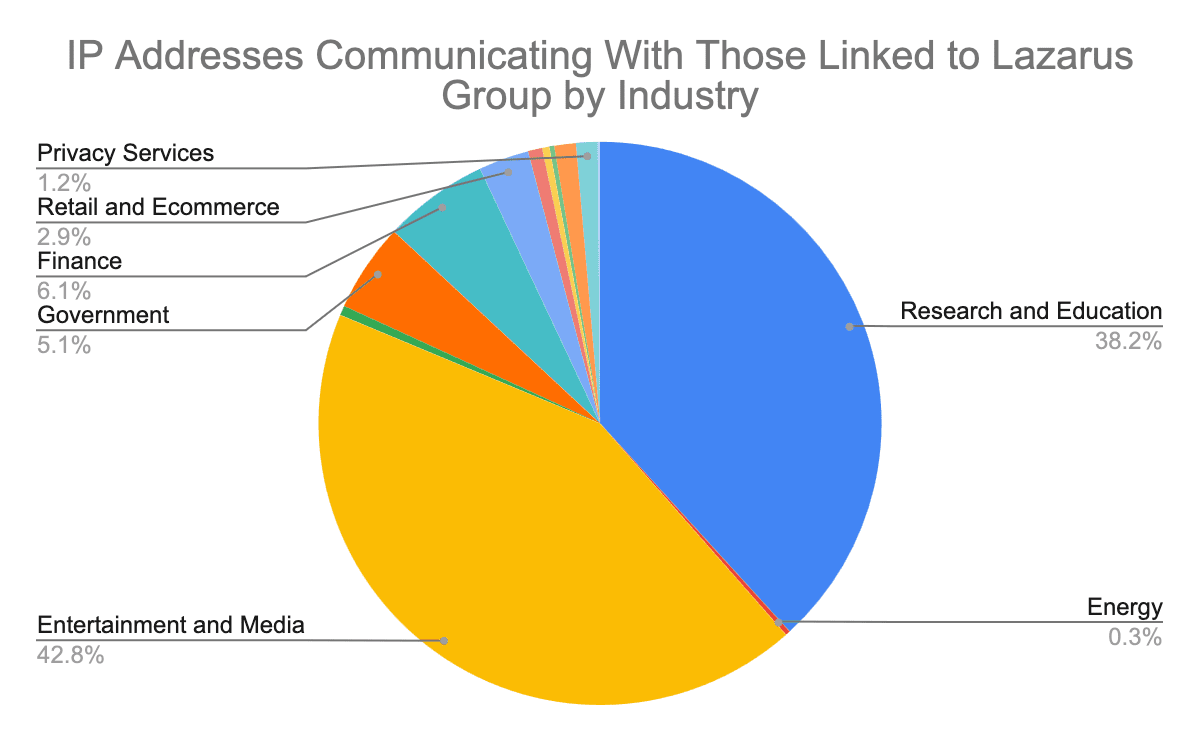

Of the remaining IP addresses, researchers identified 691 that either belong to organizations in possible target sectors, including those named in the above-cited report, such as manufacturing and energy, or others the Lazarus Group has previously targeted, including financial services and government. However, particularly large numbers of these IP addresses belonged to organizations in the entertainment and media, and research and education sectors.

Image 1: Of the 691 IP addresses most likely to yield insights about threat actor behavior, particularly large numbers belonged to research and education or entertainment and media organizations.

The original report identifies the two IP addresses from the IoC list responsible for the bulk of this traffic as possible VPN endpoints. This traffic may reflect the activity of other users in addition to the Lazarus Group, which could explain some of the trends in the traffic. For example, the communication with IP addresses belonging to organizations in the entertainment and media category (many of which are gaming companies or streaming services) could reflect attempts to access those services from jurisdictions where they would normally be inaccessible.

Similarly, although the February report noted that the recent Lazarus Group campaign targeted the higher education sector, the traffic to research and educational institutions may not reflect that activity. A great deal of web traffic still passes through educational and research institutions’ networks because these institutions furnished much of the internet’s early infrastructure and, as an inheritance of this early role, still route a great deal of traffic. That being the case, traffic to their networks does not necessarily indicate targeting.

Additionally, a strategic partner has identified many of the IP addresses belonging to some of the most heavily-represented universities in the dataset as scanners, which suggests that their communication with the IP addresses from the IoC list may represent automated activity initiated by the university IP addresses rather than targeting of those universities by the Lazarus Group.

In most cases, the traffic involving these IP addresses was less likely to merit further attention. It featured relatively brief periods of communication and small data transfers, often just a single flow of less than a kilobyte.

However, some brief exchanges may yield additional insights into threat actor behavior. For example, traffic to the IP addresses categorized as belonging to privacy services (most of which belong to the same encrypted email and VPN service) may represent threat actors’ attempts to use those services. Brief connections to such services may reflect their use, given that once a user has connected to it, their traffic would appear to be coming from an IP address the VPN uses rather than the user’s original IP address.

Additionally, three IP addresses belonging to remote access software companies appear in the dataset; threat actors have sometimes abused these services, which this communication may reflect. This traffic may help identify other tools the threat actors have used.

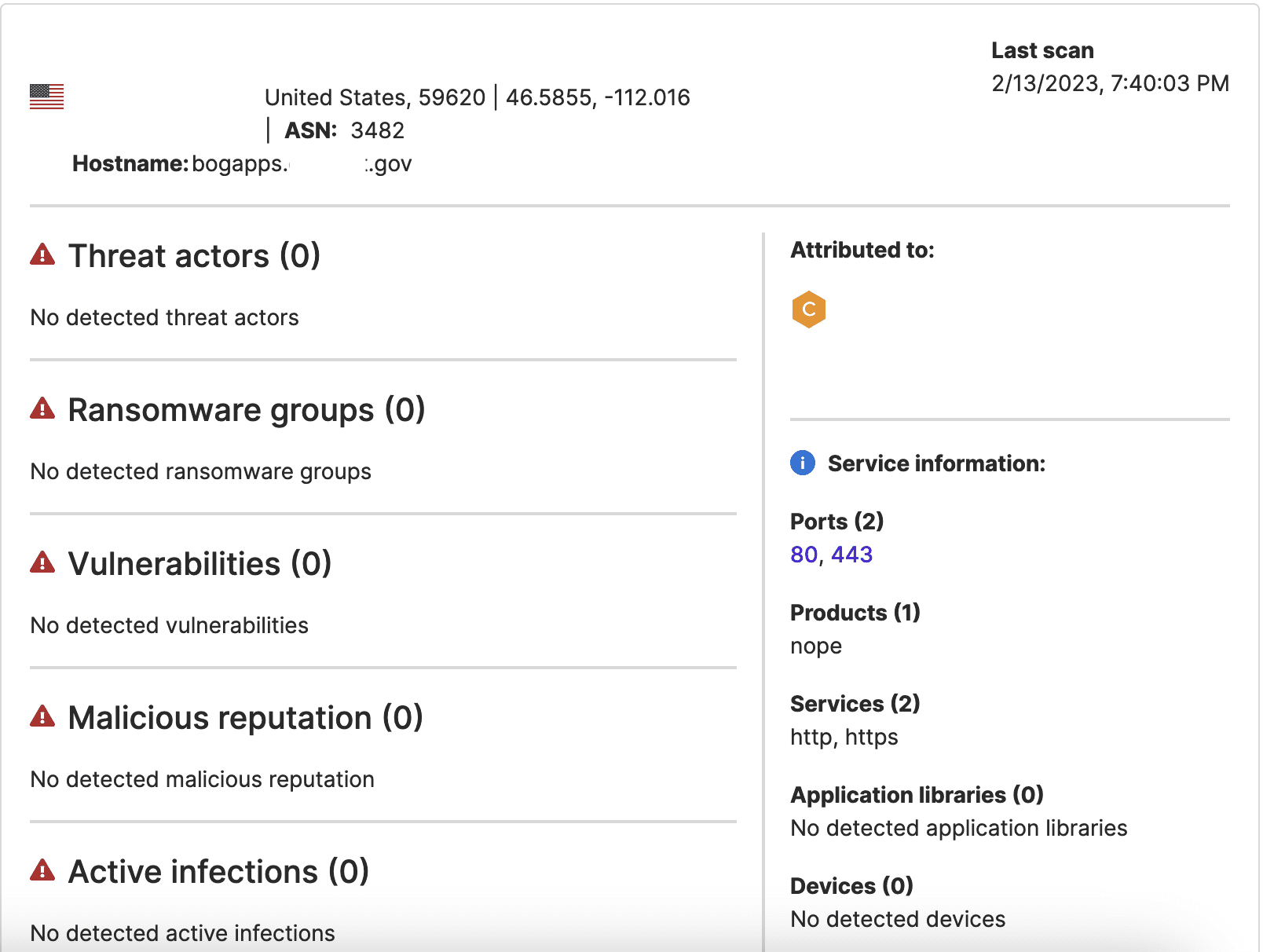

However, in the case of one state government IP address, the communication was somewhat more sustained and, therefore, more likely to be of concern. One Lazarus Group-linked IP address (23.237.32[.]34) and another IP address exchanged data 1,158 times on February 13. The available IP WHOIS data identifies a state government as the registrant organization of the IP address in question. SecurityScorecard’s Attack Surface Intelligence tool identifies a state government subdomain as its hostname.

Image 2: Attack Surface Intelligence connects the IP address with which a Lazarus Group-linked one communicated to a state government subdomain.

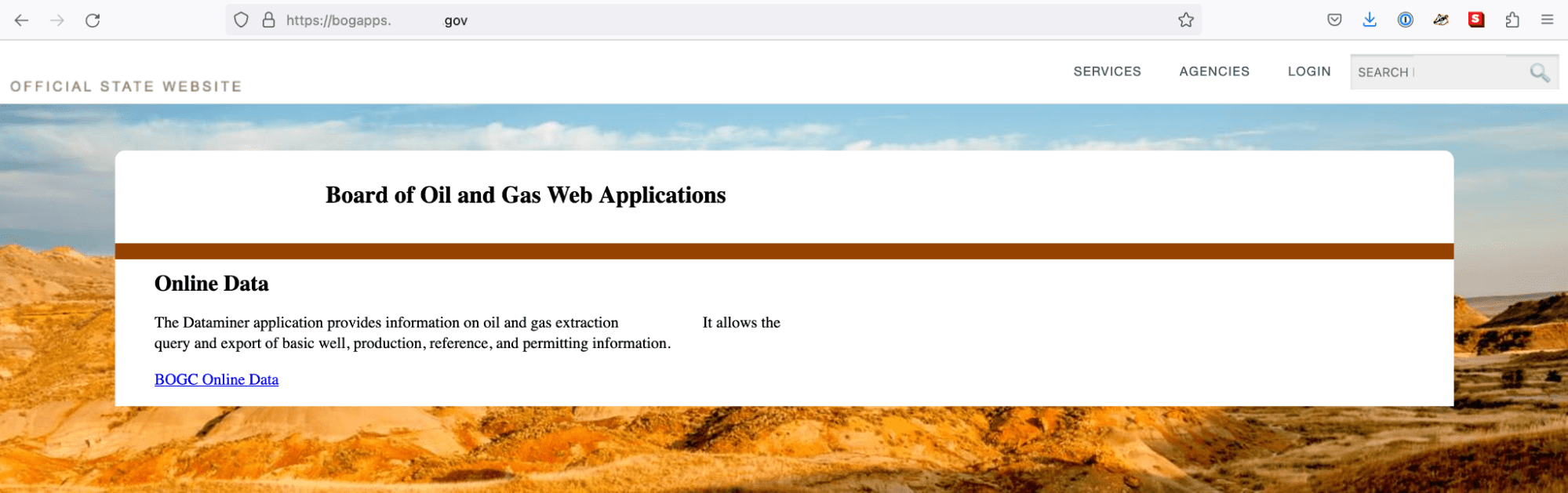

The specific subdomain identified by Attack Surface Intelligence corresponds to the state oil and gas board’s Web Applications, which offer access to data regarding oil and gas extraction.

Image 3: The state government IP address in question appears to host data regarding the energy industry.

Given that the earlier report noted that the recent Lazarus Group campaign targeted a manufacturing firm that serves the energy industry, it is possible that other organizations serving that industry or collecting data about it would also be of interest to the group. (This interest is hardly unique to the Lazarus Group; many other APT groups have also targeted the energy sector and firms surrounding it in previous campaigns).

Further review of the traffic samples revealed that another of the IP addresses linked to the Lazarus Group and a different IP address registered to the same state government communicated earlier. On January 13, at least two flows between it and 146.185.26[.]150 (a Lazarus-linked IP address) took place. The sample involving these IP addresses appears to reflect a smaller data exchange, as it only features two flows with relatively minimal byte counts. However, in light of the subsequent and considerably more numerous flows between an IP address linked to the Lazarus Group in the February report and another belonging to the state government, it could reflect an earlier stage of an attempt to access state resources.

While this data may reflect Lazarus Group activity, alternative explanations also merit consideration. The report that first linked the two IP addresses to Lazarus Group activity noted that they might be VPN endpoints, so a different VPN user may be responsible for the traffic to the state government IP addresses.

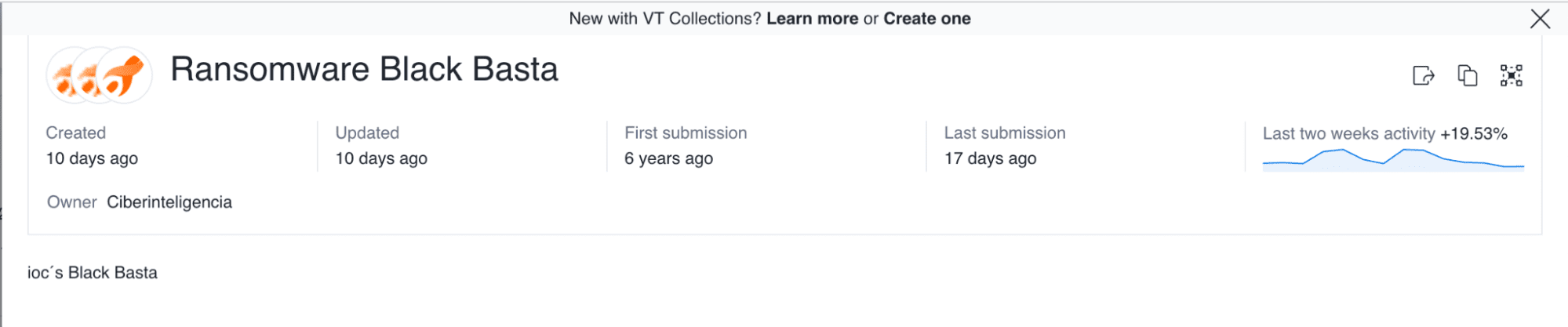

Moreover, both IP addresses belong to hosting providers, so another of their customers may be responsible for the traffic. Finally, members of the VirusTotal community have linked the IP addresses to non-Lazarus threat activity: they appear in one collection for tracking generically suspicious activity and another for tracking the activity of the Black Basta ransomware group.

Images 4-5: The IP addresses also appear in VirusTotal collections regarding activity for which the Lazarus Group is not necessarily responsible but which is nonetheless malicious or suspicious.

Conclusion

Regarding the possibility that the previous Lazarus Group activity indicated an interest in the energy sector and the inclusion of the IP address in question in a report about Lazarus Group activity, SecurityScorecard assesses with low confidence that the traffic between that IP address and one hosting state oil and gas board data reflects Lazarus Group targeting of state government assets.

However, it remains possible that other parties have also used the same IP addresses as Lazarus Group. Even if that is the case, the traffic is nonetheless suspicious, as the IP addresses involved also appear on lists tracking other threat activity in addition to that attributed to the Lazarus Group.