The Forrester Wave™: Cybersecurity Risk Ratings Platforms, Q2 2024

Cyber Risk Intelligence: Cyber Activity, Israeli Industrial Control Systems, and the Israel-Hamas War

SECURITYSCORECARD STRIKE THREAT INTELLIGENCE

Executive Summary

- Following the outbreak of war between Israel and Hamas on October 7, 2023, a wide variety of threat actors began claiming responsibility for cyberattacks against entities linked to both sides of the conflict.

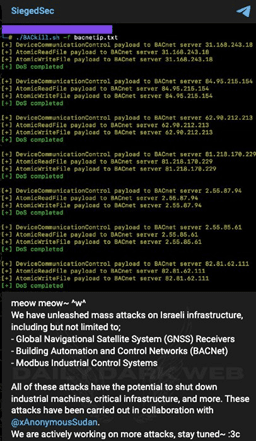

- Thus far, the attacks claimed by hacktivist groups have been relatively weak in both their impact and sophistication. However, on October 10, hacktivist group SiegedSec claimed responsibility for a series of attacks against Israeli infrastructure and industrial control systems (ICS).

- Because attacks on ICS devices could have severe consequences, the SecurityScorecard Threat Research, Intelligence, Knowledge, and Engagement (STRIKE) Team focused on those. When further investigating the cyber activity surrounding the conflict, the STRIKE Team focused on identifying other exposed Israeli ICS devices.

- As of October 11, there is no indication that the IP addresses SiegedSec listed as targets have experienced denial of service attacks.

- This could mean that these attempts were likely unsuccessful, though other explanations merit consideration.

Background

Following the outbreak of war between Israel and Hamas on October 7, a wide variety of actors began claiming responsibility for cyberattacks against entities linked to both sides of the conflict.

The available evidence offers no clear indication that cyber activity preceded physical operations. Similarly, SecurityScorecard’s recently expanded collections of Hamas-affiliated messaging channels contain no evidence of how or when Hamas’s operation would begin prior to the start of the conflict. This suggests that, in contrast to other contemporary wars, the frequency or impact of cyber and information operations did not increase leading up to the war.

Attackers quite isolated from the physical conflict and without clear operational or organizational ties to it appear to be responsible for much of the cyber conflict thus far. This isolation, along with Israel’s technological advantage over Hamas, may explain why no cyber activity preceded the physical conflict. A Russian hacktivist group may, for example, oppose Israel and be capable of attempting attacks against Israeli targets following the start of the war, but such a group would be unlikely to have a relationship with Hamas that could have offered it the early indications necessary to conduct cyber operations as a prelude to physical attacks

Thus far, the attacks have chiefly involved distributed denial of service (DDoS) attacks and website defacements, relatively low-sophistication activity typical of the hacktivist groups claiming them. However, the international scope of this activity is noteworthy, purportedly featuring Indian and Ukrainian hacktivist groups sympathetic to Israel, and claiming attacks against Palestinian organizations. But Russia- and Iran-linked groups have mounted attacks against both public and private organizations in Israel. While some of these attacks have targeted fairly high-profile organizations, their disruptive impact has been relatively minimal, especially when compared to the kinetic activity related to the conflict.

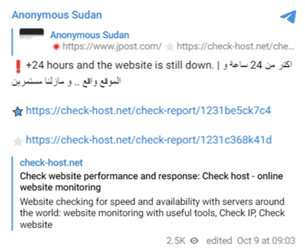

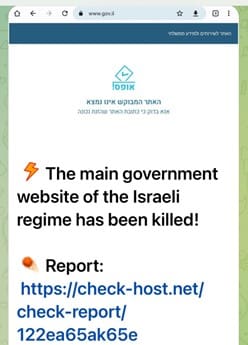

KillNet and Anonymous Sudan, hacktivist groups believed to act in support of Russian geopolitical interests, have launched some of the highest-profile attacks against Israeli targets, including: the Israeli government’s website (www.gov.il); the Israel Security Agency, better known as Shin Bet or Shabak; shabak.gov.il); and the English-language newspaper the Jerusalem Post (jpost.com).

Images 1-4: KillNet and Anonymous Sudan declared their intent to target Israeli government and media organizations and claimed attacks against them shortly after the outbreak of the conflict (sources: DailyDarkWeb, The Cyber Express, FalconFeeds.io, FalconFeeds.io

While these attacks have attracted considerable attention, they appear to have inflicted little damage beyond temporarily rendering the target organizations’ public-facing websites inaccessible. However, subsequent attempts to target industrial control systems (ICS) in Israel may offer greater cause for concern, given that disruptions to ICS devices may be more likely to have physical consequences.

On October 10, hacktivist group SiegedSec claimed that it had, in collaboration with Anonymous Sudan, conducted a series of DoS attacks against ICS devices and other Israeli infrastructure.

Attacks against ICS devices could not only compromise organizations, but may also jeopardize human lives, as ICS devices control critical infrastructure, such as power grid substations, manufacturing lines, sensors, and programmable logic controllers (PLCs), including relays and reclosers. Because such attacks could have more severe results than interruptions to websites’ service, the STRIKE Team focused on SiegedSec’s claimed targets and exposed Israeli ICS devices more generally when conducting further research and analysis into the recently-claimed attacks against Israel.

Recommendations

Speaking generally, SecurityScorecard recommends that organizations review the business necessity of exposing ICS devices to the wider Internet and, when possible, place them behind a VPN or firewall. If that is not possible, SecurityScorecard recommends that organizations consider restricting access to them by adding dependent IPs to an allow list.

To address the threat of DDoS attacks in particular, SecurityScorecard recommends the following:

- Block the IPs in SecurityScorecard’s KillNet Bot Blocklist.

- KillNet is only one of the many threat actor groups involved in the conflict, but this blocklist can likely help defend against more attackers than KillNet alone.

- Although many of the highest-profile groups involved in these attacks, including KillNet and Anonymous Sudan, likely have links to Russia, blocking Russian IPs will not stop DDoS attacks. As reflected in SecurityScorecard’s blocklist, the attacks are coming from open proxies and DNS resolvers located all over the world.

- Having only a firewall will not stop the volume of traffic we have observed in recent high-profile DDoS attacks. As a result, it’s critical to put DDoS mitigations in place via a service like Cloudflare, Akamai, or AWS Cloudfront.

- Configure DNS resolvers and proxy servers to only accept requests from internal IP addresses and authorized users, unless there is a practical reason not to do so. Much of malicious bot infrastructure relies on open proxies. If all of these services were properly configured, it would be a crippling blow to the botnet operators that support the threat actors involved in the conflict.

Findings

As of October 11, a sample of network flow (NetFlow) data provided to SecurityScorecard by a strategic partner does not indicate that the IP addresses SiegedSec listed as targets have experienced volumes of traffic consistent with a typical denial of service attack. This may support other researchers’ assessment that these attempts were likely unsuccessful, though other explanations of the relative paucity of results do also merit consideration. The strategic partner’s ability to sample traffic involving the target IP addresses may, for example, have been unusually limited. However, in the absence of reported disruptions to Israeli infrastructure, the available NetFlow sample appears to support assessments that SiegedSec’s attacks were either unsuccessful or have not yet begun in earnest.

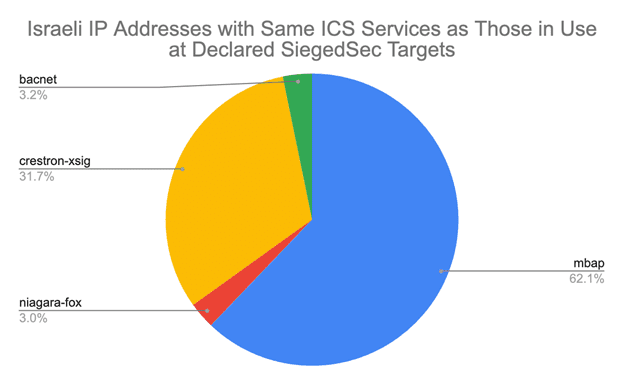

SecurityScorecard’s Attack Surface Intelligence module indicates that the following ICS services are in use at the Israeli IP addresses SiegedSec listed as targets:

- Modbus Application Protocol (mbap)

- Niagara Fox (niagara-fox)

- Crestron Intersystem Communications (crestron-xsig)

- Building Automation and Control Networks (bacnet)

In addition to those listed by SiegedSec, Attack Surface Intelligence has also identified these same services exposed at other Israeli IP addresses.

These observations indicate that mbap is the service exposed most frequently, crestro-xsig is the second most commonly exposed service, bacnet is the third, and niagara-fox is the least commonly exposed though the difference between the counts for bacnet and niagara-fox is considerably less pronounced than the others). Attack Surface Intelligence observes: 715 Israeli IP addresses where mbap is in use; 365 with observations of crestron-xsig; 37 with observations of bacnet; and 34 with observations of niagara-fox.

Users can view the affected IP addresses by running the following queries in the Attack Surface Intelligence module:

- (service:”mbap” AND country_name:”Israel”)

- (service:”niagara-fox” AND country_name:”Israel”)

- (service:”crestron-xsig” AND country_name:”Israel”)

- (service:”bacnet” AND country_name:”Israel”)

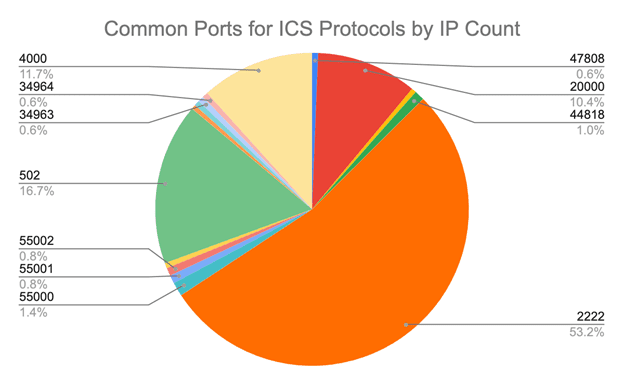

In addition to its service facet, users can also search for country-specific ICS exposures by pairing Attack Surface Intelligence’s port and country_name facets. This can potentially identify a larger number of exposed Israeli ICS devices by using the port numbers common for various ICS protocols (such as those available here) and using Israel as the country name.

These broadened queries reveal that among Israeli IP addresses, port 2222 is the most frequently exposed port used by ICS protocols (chiefly Ethernet/IP), port 502 (for Modbus TCP) is the second most-frequently exposed port, and port 4000 (for ROC PLus) is the third, with 4740, 1490, and 1040 observations respectively. Ports 55003, 34980, and 4840 (for FL-net, EtherCAT, and OPC UA Discovery Server) are the least frequently exposed, with 48, 43, and 41 observations, respectively.

The following table contains a complete collection of counts of open ports commonly used by ICS protocols observed by Attack Surface Intelligence at Israeli IP addresses:

| Protocol | Port | Israeli IP Address Count |

| Ethernet/IP | 2222 | 4740 |

| Modbus TCP | 502 | 1490 |

| ROC PLus | 4000 | 1040 |

| DNP3 | 20000 | 926 |

| FL-net | 55000 | 128 |

| Ethernet/IP | 44818 | 92 |

| FL-net | 55001 | 75 |

| FL-net | 55002 | 75 |

| BACnet | 47808 | 56 |

| PROFINET | 34963 | 53 |

| PROFINET | 34964 | 53 |

| PROFINET | 34962 | 50 |

| FL-net | 55003 | 48 |

| EtherCAT | 34980 | 43 |

| OPC UA Discovery Server | 4840 | 41 |

Conclusion

On October 9, the National Security Agency’s director of cybersecurity, Rob Joyce, noted that US intelligence has not yet observed evidence indicating that the conflict had resulted in particularly significant cyberattacks. The data SecurityScorecard gathered in the days since appears to support this assessment. While, hypothetically, attacks against ICS devices could prove more significant than many of the more visible attacks that have occurred thus far, the NetFlow data collected by the STRIKE Team does not yet point to successful attacks against the ICS targets claimed by SiegedSec. However, given the outsized impact such attacks could have on critical infrastructure, the Attack Surface Intelligence findings may merit closer attention as the conflict continues.