Cyber Risk Intelligence: LockBit 3.0 Ransomware Group Claims Defense Contractor Breach

Executive Summary

- On December 2, the LockBit 3.0 ransomware group claimed to have exfiltrated data from a major defense contractor, and threatened to leak stolen files; however, as of December 13, the supposed victim no longer appears on LockBit 3.0’s data leak site.

- Following the claim, the SecurityScorecard Threat Research, Intelligence, Knowledge, and Engagement (STRIKE) Team consulted internal and external data sources to identify evidence of a compromise.

- Publicly-shared files indicate that the claimed victim have experienced phishing attempts throughout 2022, and traffic data collected in the month before LockBit 3.0’s claim may reflect exfiltration of data from the firm’s systems.

- This traffic data, however, involves IP addresses attributed to many entities in addition to the target and may therefore reflect malicious activity affecting another organization.

- Given LockBit 3.0’s recent history of making false or exaggerated claims about its attacks and the possibility that the traffic data reflects a different attack, whether the group accessed the claimed victim’s systems and what data it stole (if any) remain open questions.

Background

On December 2, the LockBit 3.0 ransomware group claimed to have exfiltrated data from a global engineering firm and major defense contractor. The group threatened to publish the stolen files if the firm did not pay a ransom by 10:13:33 UTC (5:13:33 AM EST) on December 9. As of 11:00 AM EST on December 13, it does not appear that LockBit 3.0 has published this data. In fact, the target company’s entry no longer appears on LockBit 3.0’s data leak site. The group has, moreover, fabricated or exaggerated its claims of data theft, including claims about other defense contractors, in the recent past. Based on these previous cases, whether the group accessed the systems of the company in question and what data, if any, it stole remains uncertain.

On June 2, LockBit added an entry for cybersecurity firm Mandiant to its data leak site. Despite boasting of having stolen 356,841 files from the firm and declaring their intent to leak all of them, the group only published two files, neither of which contained Mandiant data. Mandiant reported that its own investigation did not reveal a compromise. These findings led Mandiant to hypothesize that the group was using the claim to garner publicity, which it could then use to dispute Mandiant’s then-recent assessment linking LockBit to the sanctioned Evil Corp cybercrime group. The group may have hoped to avoid the association with a sanctioned entity because sanctions can discourage victims from paying ransoms, as payments could violate the sanctions in question.

Then, on October 31, the group claimed that it had compromised the network of Thales Group, another defense contractor and threatened to leak files if it did not receive a ransom by November 7. However, by November 3, Thales stated that they had observed no evidence of an intrusion. While LockBit did not release any Thales data on the original deadline of November 7, they did leak some Thales-relevant data on November 10; the following day, Thales issued a press release denying any impact on its operations and confirming its previous assessment that the company’s IT systems did not suffer an intrusion and further explaining that LockBit had likely obtained a limited amount of data by compromising a partner account and accessing a collaboration platform.

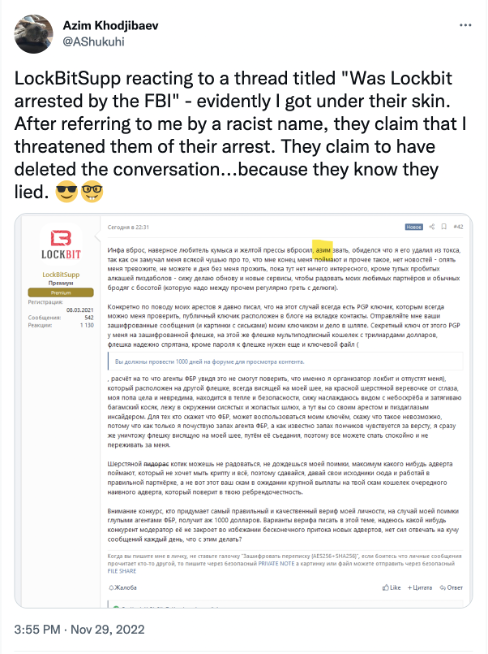

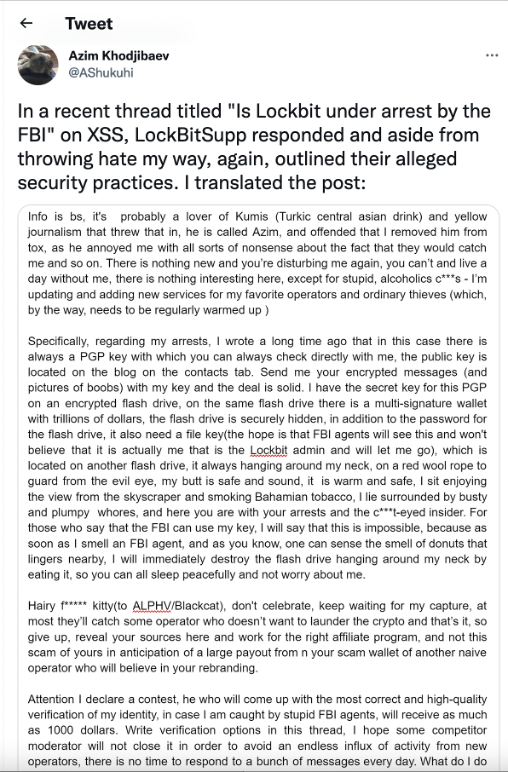

Claims that security researchers had accessed and leaked internal details of LockBit’s operations, leading to the possible arrest of a LockBit associate, may have further reduced its credibility. In September, currently suspended Twitter user @ali_qushji “said his team has hacked the LockBit servers and found the possible builder of LockBit Black (3.0) Ransomware.” Then, in late November, rumors that the FBI had apprehended one of LockBit’s operators surfaced, with cybersecurity researchers noting that a LockBit spokesperson felt the need to respond to these claims in a series of fairly lengthy posts.

Image 1: Twitter user D4RKR4BB1T47 claimed that they had contributed to the arrest of a LockBit operator on November 29

Images 2-3: A cybersecurity researcher highlights a LockBit spokesperson’s response to the rumors of the arrest on the Russian-language cybercrime forum XSS.

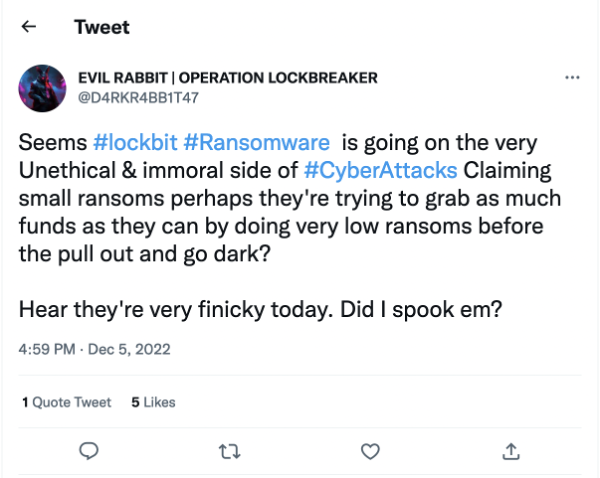

Following these claims, additional rumors that LockBit’s operators may be panicking in response to them began circulating. These rumors allege that the group had grown desperate and started “doing very low ransoms before the[y] pull out and go dark.”

Image 4: Twitter user D4RKR4BB1T47 reported on December 5 that the LockBit group may have become “finicky” in response to their previous claims.

While few details regarding these low ransoms are publicly available, it is possible that the group’s move to the “[u]nethical & immoral side” of ransomware by “claiming small ransoms” may also involve claiming relatively small or low-impact breaches (as in the purported Thales Group compromise) from a larger pool of supposed victims in an effort to cast a wider net and improve their odds of extracting payments by seeking them from more organizations.

These events suggest that LockBit 3.0 may also be making exaggerated or false claims of a breach in this more recent case. However, unlike Thales, the company has not publicly responded to LockBit 3.0’s claim. The organization may not have commented yet because incident response efforts are ongoing; the company may not issue a statement confirming or denying the claim until the conclusion of its own investigation into the purported incident. However, the firm may assess LockBit 3.0’s claims as not worth dignifying with a response. The group’s previous false or exaggerated claims may, when considered alongside the recent rumors that researchers had hacked its servers and assisted in the arrest of a LockBit group member, have so damaged its credibility with its extortion targets that the company sees no need to engage with the group.

LockBit TTPs:

The LockBit group has operated since 2019 and uses a ransomware-as-a-service (RaaS) business model in which affiliates earn a percentage of the ransoms collected by the ransomware strain’s developers and leak site operators by accessing and deploying the group’s titular strain of malware to target systems. The group first rebranded as LockBit 2.0 in January 2021 before rebranding again as LockBit 3.0/LockBit Black in Spring 2022. Analysis of a LockBit sample published in July 2022 revealed similarities between it and the BlackMatter and DarkSide strains of ransomware (the latter having acquired considerable infamy for its role in the May 2021 Colonial Pipeline attack) and noted that in the incident during which that sample appeared, attackers initially accessed the target network using a spearphishing attachment. More recent findings suggest that the group has continued to use a similar technique: on December 12, a cybersecurity researcher reported that they had observed LockBit spreading through malicious documents (maldocs), which attackers often distribute through phishing. While STRIKE observed evidence of phishing against the claimed victim (discussed below), it does not appear to specifically indicate the use of maldocs that lead to downloads of the LockBit ransomware.

Phishing Against Target Company

STRIKE researchers consulted data available in the public cybersecurity information-sharing platform VirusTotal, reviewing files submitted throughout 2022, which likely reflect phishing attempts against LockBit 3.0’s target. These mainly appear to be HTML files containing JavaScript, which likely redirected users to credential-harvesting pages or pages serving downloads of information-stealing malware (infostealers). While these are unlikely to have led directly to the deployment of ransomware, they could have provided attackers with credentials they could later use to access target systems and subsequently deploy ransomware to them.

A series of HTML files containing company email addresses, which may reflect phishing attacks against the company, appeared on VirusTotal between January and March 2022. The first such file appeared on January 12, which vendors have linked to phishing and malicious JavaScript. Its title refers to a remittance payment to the same employee whose email address the file contains–attackers likely used payment information as a lure in this case. Another file with similar detections but containing a different employee’s email address appeared on February 1. The same email address appeared again in a file submitted on February 10, which also contains a domain detected for phishing. Two additional files, which appeared on March 25 and 29, feature other email addresses and JavaScript redirecting to malicious URLs or malicious downloads. A file similar to the one submitted on March 25 appeared on July 7; it, too, contains a company email address and an apparently malicious redirect.

Another July email may reflect a phishing attempt that also informed a later compromise. That email is addressed to a firm employee and refers to an attachment called “payslip.html.” The title may indicate that it is a phishing lure intended to attract the recipient’s attention by offering them information about their paycheck, and the use of an HTML file as an attachment could reflect HTML phishing, the practice of directing targets to malicious links leading to credential-harvesting or other phishing forms through seemingly benign (and easy-to-obfuscate) attached HTML files rather than by directly including a link to the malicious page in the body of an email, where a user may more easily notice that something is amiss. The same email address appeared again in the title of another HTML file submitted on November 8, which six vendors have linked to phishing. This could reflect an attempt to phish others in the company by using a compromised employee email account to send phishing messages, or it could reflect another attempt to target the same employee with a different lure.

While, speaking broadly, these files resemble the LockBit 3.0 techniques identified above in that they both involve phishing and malicious attachments, these files are more likely to have enabled credential theft than the deployment of ransomware. However, it is fairly common for ransomware operators to use stolen credentials to access target systems, so while these files may reflect reconnaissance (the attempted collection of target credentials) rather than initial access (their use to access a system), they could still feasibly have supported a ransomware group’s efforts. As a RaaS operation, it is likely that different LockBit 3.0 affiliates employ different techniques to access target networks, so the dissimilarities in initial access techniques do not necessarily disprove LockBit 3.0’s claims. However, by the same token, though they could also reflect activity unassociated with ransomware–for example, the references to payslips and other financial matters could indicate an attempt at business email compromise (BEC).

Traffic Analysis

In a one-month monitoring period, SecurityScorecard’s strategic partner observed more than 100,000 data transfers between IP addresses SecurityScorecard attributes to the company and 1,389 IP addresses where this partner has observed botnet malware operating. Not only is it fairly common for botnet operators to act as initial access brokers for ransomware operators, but multiple actors can also use the same IP addresses for different purposes, so this traffic could reflect later stages of an attack in addition to an initial compromise. Further reflecting the possibility of their involvement in more varied malicious activity, vendors have linked 313 of the observed IP addresses to malicious activity and identified twenty-three of them as TOR exit nodes.

Much of the communication indicated large transfers of data to suspicious IP addresses. This likely indicates an attacker’s exfiltration of data from a victim network. SecurityScorecard, therefore, assesses with high confidence that one of the organizations using those IP addresses suffered a compromise. However, these transfers do not necessarily support LockBit 3.0’s claims of having stolen data from this particular firm: the apparent victim IP addresses involved in these transfers are shared resources that SecurityScorecard attributes to at least 1,000 entities, including other claimed ransomware victims.

Image 5: SecurityScorecard’s Attack Surface Intelligence (ASI) tool indicates that SecurityScorecard attributes one of the IPs apparently used by the target company to 1,000 different entities, including multiple ransomware victims.

Thus, while this traffic likely reflects data theft from one of the entities to which SecurityScorecard attributes these IP addresses, it may not specifically reflect a LockBit 3.0 affiliate’s theft of data from this particular company.

Conclusion

Files submitted to VirusTotal throughout 2022 indicate that threat actors have attempted to phish employees of the target organization. Although using spearphishing to distribute malicious files is an established initial access technique for LockBit affiliates, phishing is by no means unique to the group. Similarly, while the traffic data STRIKE collected likely reflects data theft, it is not clear that the theft specifically involved LockBit 3.0 and this company, as SecurityScorecard attributes the affected IP addresses to many other entities in addition to it. In light of these considerations and LockBit 3.0’s recent history of making false or exaggerated claims about its attacks, whether the group accessed this defense contractor’s systems and what data it stole (if any) remain open questions.

Next Steps

Given that the LockBit group appears to have based its previous claim of having exfiltrated Thales Group data upon a third-party breach (one which Thales described as fairly minor), it is additionally possible the group is also basing these newer claims upon similar data. SecurityScorecard’s products and services can help organizations like Thales reduce the risk of future third-party breaches by enabling proactive and reactive investigative services and continuous monitoring of their partner organizations and resources they share with them.

Digital Forensics and Incident Response

SecurityScorecard provides incident response and digital forensics teams as a professional service driven by a large group of former law enforcement and private sector experts with decades of experience in the space. For immediate support from our teams, please contact us.

Cyber Risk Intelligence

SecurityScorecard Threat Research, Intelligence, Knowledge, and Engagement (STRIKE) Team could furnish the competitive advantage firms need to stay ahead of today’s fast-moving threat actors. For more custom insights from our team with 100+ years of combined threat research and investigation experience, or more details on these findings, please contact us for a discussion of our Cyber Risk Intelligence as a Service (CRIaaS) offering. This investigation should be considered trustworthy but preliminary, and our team can continue diving into these details, especially with the ability to support further by working with on-site staff.

Security Ratings

SecurityScorecard’s ratings platform offers organizations critical insight into vulnerabilities present both in their own environments and the environments of their vendors, partners, suppliers, and other third parties. Aside from providing clarity on the nature of risks in their risk ecosystem, security ratings provide tangible cost savings both in operating expenses and staff time. SecurityScorecard enables efficient scaling of ecosystem risk management programs in the following ways:

- The process of evaluating a new vendor is a minefield of uncertainty, but security ratings allow organizations to effectively and easily benchmark vendors and partners.

- Instant security ratings allow organizations to make instant decisions. SecurityScorecard’s on-demand reporting allows businesses to base their decisions on data from today’s reality, not on a stale report from an assessment period, possibly several months ago. This can identify current first- and third-party risks to organizations and help them address pressing concerns rather than spending resources remediating outdated vulnerabilities.

Significantly, 97 percent of the data on which our ratings and services are based is sourced from in-house collection and analysis operations:

- Our global internet scanning framework scans 3.9 billion routable IP addresses every 10 days across more than 1400 ports. It shows the internet from a threat actor’s point of view, including:

- IP addresses

- Exposed port mappings

- Fingerprints of services, products, libraries, operating systems, devices, and other internet-exposed resources, including version numbers

- Common Platform Enumeration (CPE) IDs

- Common Vulnerability Enumeration (CVE) Version 2 IDs

- Our malware DNS sinkhole provides Information about infections from more than 150 malware families without requiring an inside sensor on infected systems or networks.

- Our malware attribution system provides automated malware analysis, classification, and tracking at a large scale. This includes rich information about malware families, threat groups, and campaigns, enabling us to generate issue types and track threat groups.

- Our leaked records service provides 68 terabytes of processed data, including user names, passwords, social media URLs, Social Security numbers, credit card numbers, addresses, IPs, and more, all leaked in breaches of various files and sources. It yields more than 600 normalized .jsonl data files and 10 billion records.

- Our ransomware leak site crawler provides findings specific to ransomware attacks, breaches, and credential leaks. It also provides insight into how the ransomware groups operate, what industries they target, who the victims are, and what data is stolen. We actively track and update information on more than 40 active ransomware groups daily.

- Our honeypot system provides information about the structure and intentions of advanced persistent threats (APTs) and ransomware groups that actively exploit a particular vulnerability.

- Our Chrome-based web crawler gathers information on all major sites’ infrastructure, vulnerabilities, vendor dependencies, screenshots, and more.

- It detects supply chain dependencies in software and provides data for more than 50 issue types in the Application Security factor.

- MISP (malware information sharing platform) Threat Sharing is an open-source resource that provides key information in ASI related to threat actors and malicious IP reputations.

Attack Surface Intelligence

While our security ratings offer a somewhat filtered view of the above data by presenting it in easy-to-understand A to F scores based on ten key risk factors, SecurityScorecard’s Attack Surface Intelligence (ASI) puts that data directly into users’ hands and gives them the power to run custom queries based on industry, threat actor, IP and more. ASI thus expands and fuses traditional external attack surface management and threat intelligence capabilities to illuminate and contextualize what threat actors, including ransomware groups, are doing and how it can affect firms and anyone in their business ecosystems (such as third- and fourth-party vendors). Through the ASI lens, they can gain a comprehensive view of threat activity around the world and then zoom in to connect that activity to a single IP address, port, vulnerability, and many other data points.

Blueprint for Ransomware Defense

On August 4, the Institute for Security and Technology’s (IST) Ransomware Task Force (RTF) announced the release of its Blueprint for Ransomware Defense – a clear, actionable framework for ransomware mitigation, response, and recovery aimed at helping organizations navigate the growing frequency of attacks.

SecurityScorecard is proud to be the only security ratings platform to sponsor and participate in the development of The Blueprint and is one of only five organizations that participated in the program’s development.

You can see the Blueprint for Ransomware Defense here.