LockBit Ransomware Group Claims Attack Against Prominent Taiwanese Semiconductor Firm

Executive Summary

- On June 29, the LockBit ransomware group added an entry for a major semiconductor manufacturer to its data leak site.

- In response, the named firm denied that an attack had compromised customer data or affected its operations. Instead, it reported that an attack against a hardware supplier had exposed a limited amount of its data.

- The SecurityScorecard Threat Research, Intelligence, Knowledge, and Engagement (STRIKE) Team consulted internal SecurityScorecard data, a strategic partner’s traffic data, and public reporting on the incident to offer further insight into these claims.

- STRIKE Team researchers identified suspicious activity affecting both companies. The available data does not necessarily confirm LockBit’s claims, but it could reflect malicious activity. Therefore, it merits review by personnel with internal visibility into the affected firms’ networks.

Background

On June 28, a LockBit-associated threat actor known as “Bassterlord” claimed to have mounted a ransomware attack against a major semiconductor manufacturer and posted screenshots suggesting access to its systems in a series of since-deleted tweets. An entry for the company appeared on LockBit’s data leak site the following day. In the wake of these claims, the company denied that the attack had affected its operations or exposed customer data. Instead, it reported that an attack against a hardware supplier had exposed a limited amount of its data.

LockBit is a ransomware-as-a-service (RaaS) group that has operated since 2019 and rebranded twice, first as LockBit 2.0 in January 2021 and again as LockBit 3.0 or LockBit Black in Spring 2022. In March 2023, the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) issued a #StopRansomware alert about the group in which it identified remote desktop protocol (RDP) compromise, drive-by compromise, phishing, abuse of valid accounts, and exploitation of public-facing applications as initial access techniques observed in LockBit attacks. The alert also noted that the group has used a custom tool, Stealbit, and web services for data exfiltration.

In Summer and Fall 2022, LockBit made several false or exaggerated breach claims against prominent organizations. The group added an entry for Mandiant (a large cybersecurity firm that Google has since acquired) to its data leak site in June 2022. Despite initially boasting of having stolen a large number of files, the group ultimately only released two files, neither of which contained Mandiant data. Following an internal investigation that revealed no evidence of compromise, Mandiant hypothesized that the group was using the claim to garner publicity in hopes of leveraging the attention to dispute Mandiant’s then-recent assessment linking LockBit to the sanctioned Evil Corp cybercrime group.

Then, on October 31, the group claimed that it had compromised the network of defense contractor Thales Group and threatened to leak files if it did not receive a ransom by November 7. However, by November 3, Thales stated that they had observed no evidence of an intrusion, and LockBit did not release any Thales data on the original deadline of November 7. The group did leak some Thales-relevant data on November 10, after which Thales issued a press release denying any impact on its operations and confirming its previous assessment that the company’s IT systems did not suffer an intrusion and further explaining that LockBit had likely obtained a limited amount of data by compromising a partner account and accessing a collaboration platform.

Similarly, on December 2, the group claimed to have exfiltrated data from another major defense contractor. Initially, LockBit threatened to publish the stolen files if the firm did not pay a ransom by December 9. However, LockBit never published this data and eventually removed the company’s entry from its data leak site.

Despite the possibility that LockBit has again exaggerated its claims, the STRIKE Team consulted internal SecurityScorecard data, a strategic partner’s traffic data, and public reporting on the incident to offer further insight into the group’s recent claims.

Findings

STRIKE Team researchers identified suspicious activity affecting both the semiconductor manufacturer and its supplier. The available data does not necessarily confirm LockBit’s claims but could reflect malicious activity.

Researchers observed extended communication between a manufacturer-attributed IP address and three foreign IP addresses belonging to organizations without clear business relationships with it. All of these exchanges used the Internet Control Message Protocol (ICMP), which has legitimate uses but appears relatively infrequently in the traffic samples the STRIKE Team analyzes.

In this particular dataset, communications with these three IP addresses are responsible for almost all flows over ICMP; this traffic therefore appears strange, if not malicious. It further bears noting that threat actors can use ICMP for command and control (C2) communications, which these flows may reflect.

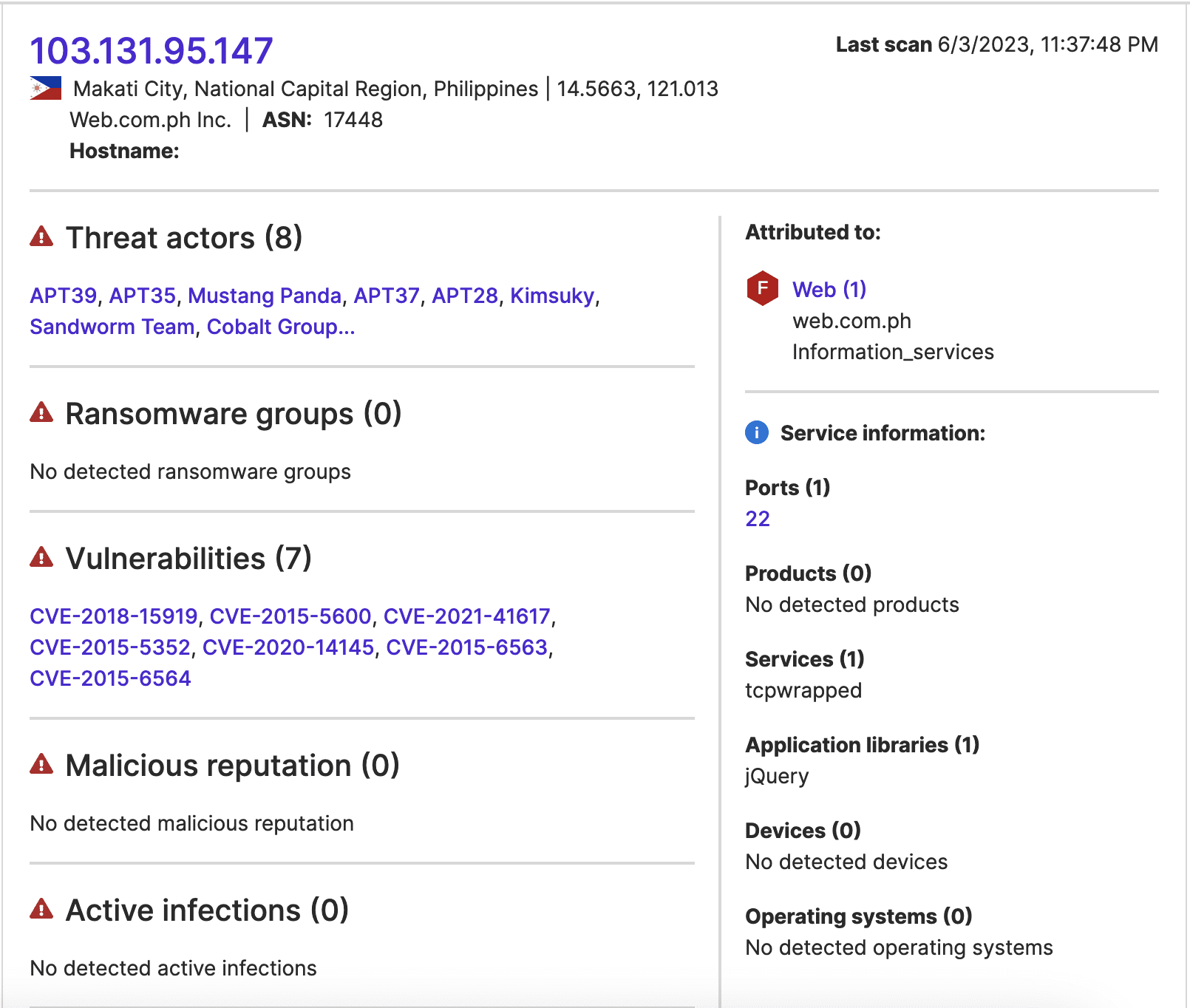

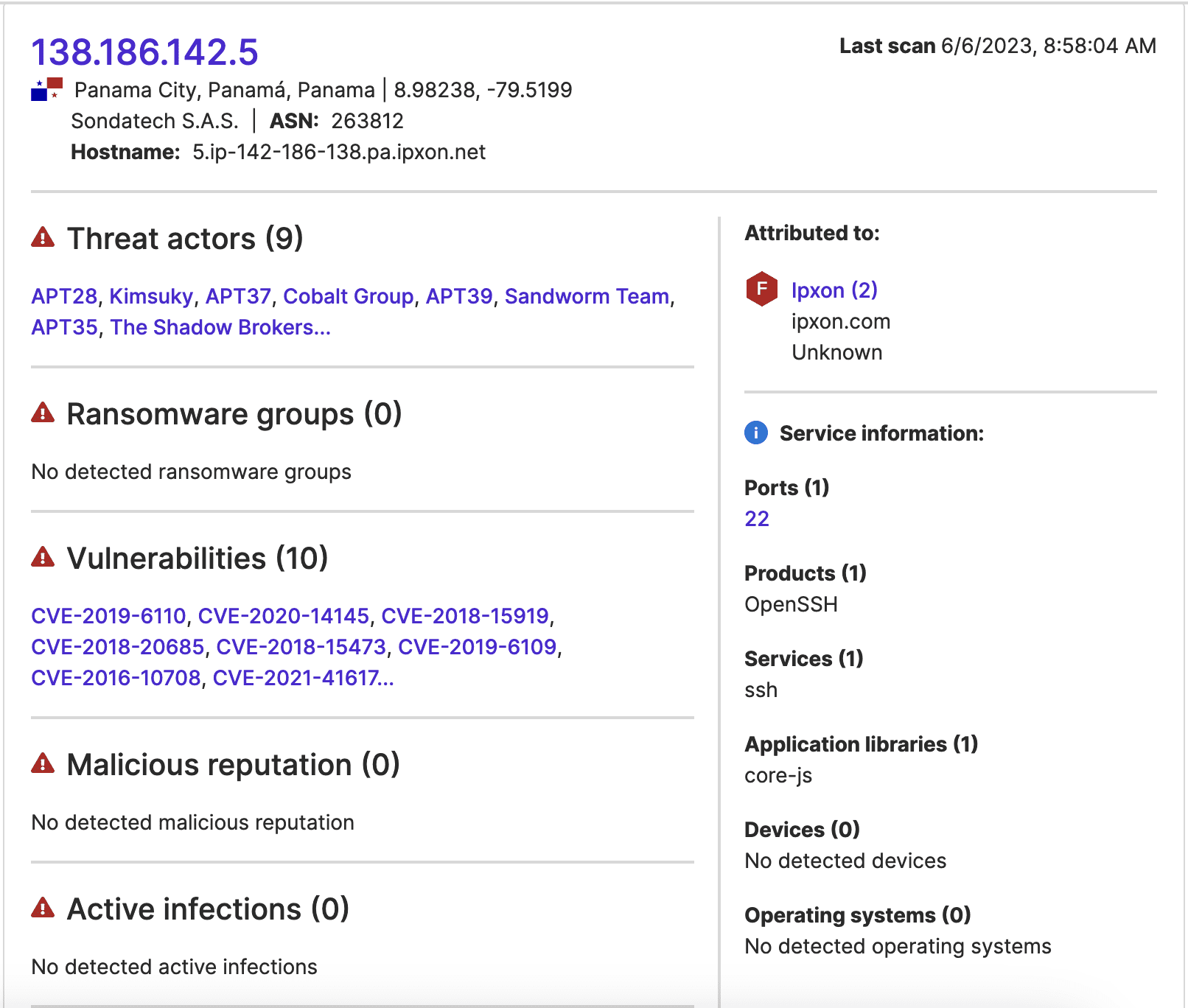

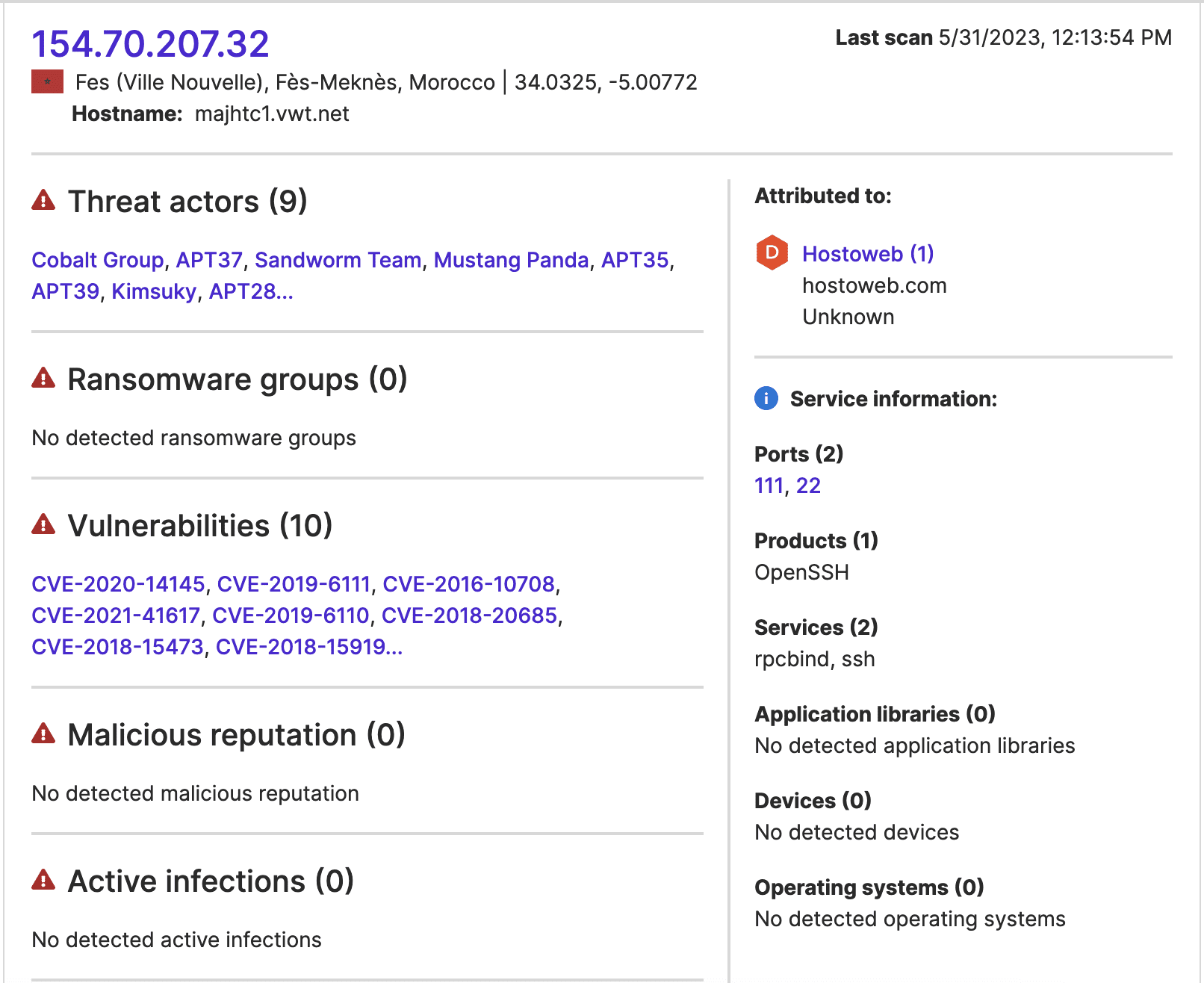

Port 22 was additionally open and running vulnerable software at all the external IP addresses involved in these communications. So, it is possible that threat actors accessed these IP addresses over SSH (possibly by exploiting the observed vulnerabilities) and then subsequently used them to communicate with the manufacturer IP address involved.

Images 1-3: SecurityScorecard’s Attack Surface Intelligence module indicates that vulnerable ports were open at three IP addresses that established extended connections with an IP address attributed to the semiconductor manufacturer.

In addition, researchers observed sixty transfers larger than 50 MB from manufacturer-attributed IP addresses to thirty-nine IP addresses that belong to a large hosting provider. While traffic to these commercial servers could reflect transfers to backups or other benign activity, given that large transfers can also represent exfiltration, in light of the circumstances, review by personnel with internal visibility into the affected company’s network is likely appropriate.

The supplier’s traffic sample revealed that it experienced considerable suspicious activity. The majority of flows in the sample (10,751 of 14,118 ) saw two supplier-attributed IP addresses contacting 209.197.3[.]8, which ten vendors who contribute detections to VirusTotal have linked to malicious activity. Although it belongs to a legitimate content delivery network (CDN) and serves legitimate downloads, members of the cybersecurity community have also observed various strains of malware communicating with this IP address. That being the case, the regular contact between it and supplier-attributed IP addresses may suggest malware infections on devices at the IP addresses attributed to the hardware supplier. These infections could have led to the theft of credentials that attackers leveraged in a later stage of the attack or the delivery of ransomware as a later stage payload.

The sample additionally contains 80 instances of communication between supplier-attributed IP addresses and addresses that the strategic partner that provides SecurityScorecard’s traffic data identifies as proxies or virtual private network (VPN) or TOR exit nodes from May 9 to July 1. While communication with proxies such as these is not necessarily malicious, given that threat actors often use them, some of these flows could reflect the activity that culminated in the breach that the supplier disclosed.

Port 25 of another IP address attributed to the hardware supplier communicated particularly frequently with VPN-linked IP addresses on May 25, May 27, and June 1. Other traffic may additionally suggest that the targeting of port 25 was more extensive. It repeatedly communicated with foreign IP addresses between May 5 and July 3, experiencing fifty-four notably long sessions and sixty-six sessions featuring data exchanges across multiple client ports. These could also reflect the operation of malware within the supplier’s network, as information-stealing malware (which can compromise credentials for subsequent use by attackers) sometimes uses SMTP, which usually runs at port 25, for command and control (C2) communications or exfiltration.

STRIKE Team researchers additionally identified a group of transfers of 10 MB or more from supplier-attributed IP addresses, which could reflect exfiltration. These included eight flows of 12.29 MB to a group of IP addresses that included some identified as VPN nodes between May 25 and June 20, one 11.63-MB transfer to 146.190.226[.]176 on June 11, and three 10.26-MB transfers from 165.227.153[.]96, 139.59.162[.]165, and 161.35.153[.]99 on May 24, 29, and 30. While the uniform size of some of these transfers could suggest that they represent routine behavior, given the supplier’s confirmation of a breach, they may merit further investigation as they could include IP addresses that threat actors used to steal the data exposed in the breach.

Files contained in the cybersecurity information-sharing platform VirusTotal also suggested that both companies have experienced suspicious activity over the past year, though none are clearly connected to the recent claim.

A PDF file of an email dated June 26, which may reflect phishing targeting the semiconductor manufacturer, appeared on VirusTotal on June 27. Phishing messages often attempt to provoke hasty action in their recipients by discussing what appear to be urgent matters. In this case, the message’s discussion of sudden changes to an interview about employees’ visa applications could indicate such an attempt. While this file may be less likely to represent phishing because it currently has no detections in VirusTotal, another that contains a company email address and appeared in VirusTotal on April 25 is likely malicious. Thirty vendors detect it as malicious, and many of these detections link it to phishing. It is an HTML file containing input fields for an email address and password, which suggests that it corresponds to a credential-harvesting page distributed either via a malicious link or HTML phishing. A manufacturer email address appears in the file’s title, suggesting that it targeted the particular employee whose email address the title contains.

The available files suggesting targeting of the hardware supplier appeared in VirusTotal earlier than those containing the manufacturer’s domain. Two files suggesting a compromise of a supplier email account appeared in October 2022. Two vendors have linked each file to phishing, and both contain the same supplier email address in the “from” line. This may suggest a threat actor had compromised the email address contained in the files and used it to distribute phishing emails to targets at other organizations.

Prior to these, a file that four vendors detect as malicious and which communicated with multiple supplier domains appeared on VirusTotal in August 2022. Two of these detections (Ransom.Win64.Wacatac.sa and BehavesLike.Win64.Ransom.wc) suggest a connection to ransomware. Still, given the timing of the submission to VirusTotal relative to the date of the breach announcement, it is unlikely that this file is related to the recent incident. It may nonetheless suggest that previous malicious activity affected the company and could offer additional background information regarding the targeting of the company.

Methodology

STRIKE Team researchers leveraged network flow (NetFlow) data furnished by a strategic partner to collect samples of traffic involving IP addresses attributed to the semiconductor manufacturer and its hardware supplier. Researchers included all of the IP addresses SecurityScorecard’s ratings platform attributes to the supplier (nineteen in total). However, due to the constraints of the NetFlow tool available, collected traffic samples for relatively small fractions of the more than 6,000 IP addresses attributed to the manufacturer.

Researchers collected samples from two groups of manufacturer-attributed IP addresses. The first consisted of IP addresses where SecurityScorecard detected issues, given that threat actors may be more likely to target IP addresses affected by the issues SecurityScorecard observes. The second consisted of manufacturer-attributed IP addresses ending in 31, as a screenshot provided by the threat actor claiming the breach appeared to contain an IP address ending in 31.

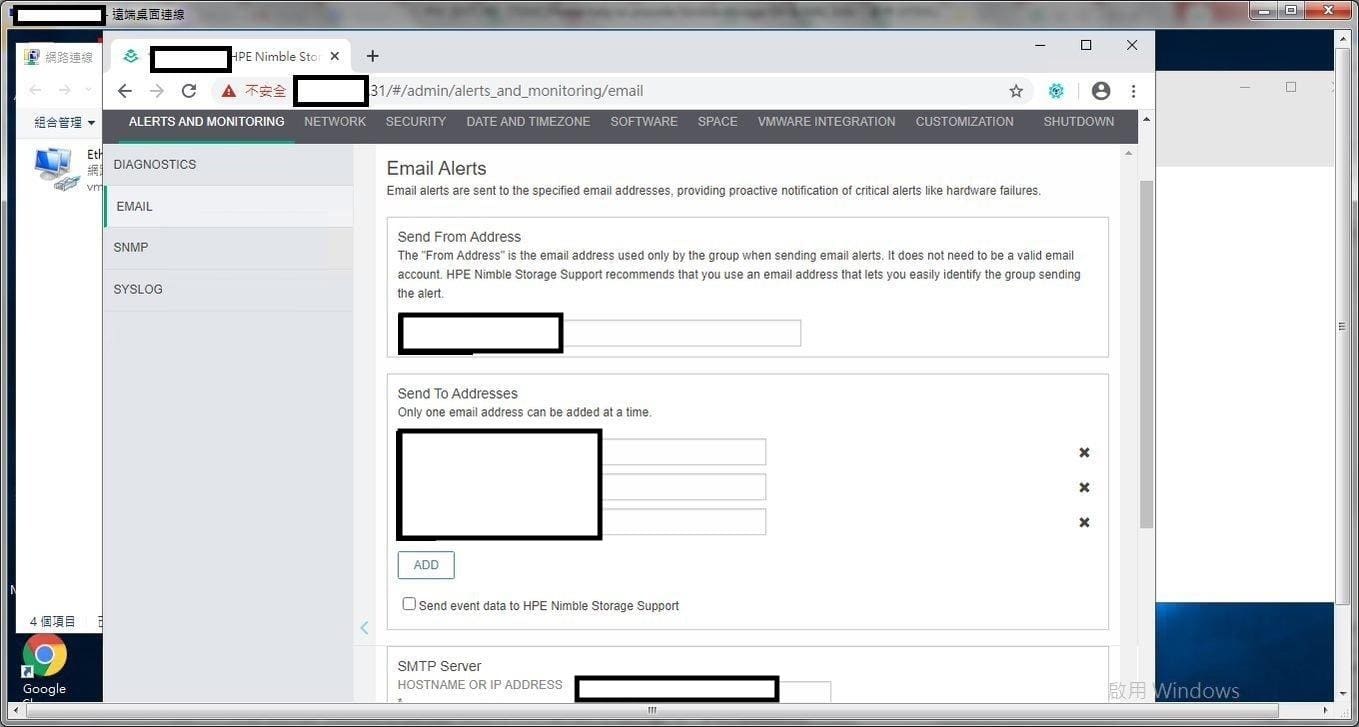

Image 4: The LockBit associate who first claimed the attack included this screenshot to prove their access to manufacturer systems (source: VX-Underground).

Publicly-available reporting on the incident indicates that threat actors provided a screenshot alongside the claim of the attack, which purportedly proves their access to manufacturer systems and displays a browser’s address bar. The address in the published version of the screenshot is mostly obfuscated but appears to end in 31. According to SecurityScorecard’s digital footprints, seventy-two IP addresses attributed to the manufacturer end in 31, but none attributed to the supplier do. STRIKE Team researchers, therefore, collected and analyzed a traffic sample for these seventy-two IP addresses to assess the possibility that the screenshot reflected a compromise of any of these manufacturer-attributed IP addresses, which could suggest that the breach affected the manufacturer itself in addition to its supplier. STRIKE Team researchers collected this sample to further assess this possibility.

Finally, STRIKE Team researchers searched for files containing both firms’ domains in VirusTotal to identify other evidence of malicious activity.

Conclusion

While the available information may suggest that both the supplier and the manufacturer experienced suspicious activity, it does not necessarily confirm LockBit’s claims to have compromised the semiconductor manufacturer’s systems. It first bears noting that suspicious traffic constitutes a much larger portion of the supplier’s traffic sample than either of the manufacturer’s traffic samples and may therefore be more likely to indicate compromise, which could support the manufacturer’s explanation that the supplier’s breach exposed some of the manufacturing company’s data. However, LockBit may additionally have exaggerated or fabricated its claims. As discussed above, LockBit has previously made false or overstated claims of breaches affecting politically-relevant firms like defense contractors.

Given the strategic importance of the Taiwanese semiconductor industry, and increasing public awareness of the geopolitical sensitivities surrounding the industry, LockBit may be attempting to take advantage of increased attention to the semiconductor manufacturer and extract a payment from it based on the publicity their claim generated rather than the amount of data accessed.

This incident is comparable to LockBit’s November 2022 attempt to extort Thales Group. In that case, LockBit claimed to have compromised Thales Group but had, according to Thales, only accessed a comparatively small amount of the company’s data that a third party had exposed. In this one, LockBit has added an entry for a prominent semiconductor manufacturer to its data leak site, but the named company has linked the compromise to a supplier that has confirmed that a breach recently exposed its customers’ data.