SecurityScorecard also found that 1 in 5 of the world’s food processing, production, and distribution companies rated have a known vulnerability in their exposed Internet assets

Key insights

Using SecurityScorecard’s proprietary tools, our Investigations & Analysis (I&A) team observed the following:

- The JBS campaign began with a reconnaissance phase in February 2021, followed by data exfiltration from March 1, 2021, to May 29, 2021, and finally, the threat actors encrypted their environment on June 1st. This is the first time that data exfiltration, for this attack, has been identified.

- There are indications that JBS was a targeted attack conducted by the REvil ransomware group. Both JBS Brazil and JBS Australia were targeted as part of such operations.

- The attack started in JBS Australia as a data exfiltration point. We identified a JBS Australia domain associated with JBS operations in Australia.

- We observed data exfiltration from JBS Australia in excess of 45 GB of data to the file-sharing site known as Mega.

- From there, we uncovered evidence of further data exfiltration from JBS Brazil to the same Mega file transfer service used for Australia. This further confirms the underground chatter indicating that operations in Brazil were also targeted as part of this intrusion. The observed data transfer occurred between April 19 to May 25.

- We observed additional exfiltration at a potential loss of data amounting to 5 TB during the course of three months. Data exfiltration occurred multiple times during this period to Mega and other known malicious IPs in Hong Kong that are not associated with JBS.

- While the exact intrusion vector is unknown, our analysis looked for potential avenues for intrusion. Typically before an intrusion, there is a phase of reconnaissance to assess possible entry points. We observed data reconnaissance operations occurring prior to the actual data exfiltration.

- 1 in 5 of the world’s food processing, production, and distribution companies have a known vulnerability (i.e., a Common Vulnerability and Exposure or “CVE”) in their exposed Internet assets. This puts the global food supply chain at risk.

Background

The SecurityScorecard Investigations & Analysis team (I&A) investigated reports of the ransomware breach on JBS, one of the world’s largest meat processors. The scope of our investigation is focused on understanding the attack and the adversary was behind it to help others respond and better protect themselves from ransomware threats. Further, we wanted to understand if data exfiltrated out of the environment could further be used to leak sensitive data on the dark web.

Our investigation was primarily centered around understanding the scope of the breach, potential attribution, and any other findings that might provide insight into what occurred. Further, the attack has been reported to have been carried out with the Sodinokibi Ransomware, a variant of ransomware used by the REvil ransomware group, suspected to be attributed to Russia.

The U.S Government confirmed on June 3, 2021, that the REvil / Sodinokibi group was responsible for the attack.

CVEs (Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures) are known problems in software that could lead to system compromise. Some are relatively benign (representing a small risk) while others are very serious and leave a system open to takeover. The skillset required to exploit these vulnerabilities varies from basic to extremely advanced. The risk a vulnerability poses is a combination of the vulnerability itself and the skill needed to exploit it.

Access and reconnaissance

One outstanding question is what the potential initial intrusion vector was. There are multiple plausible theories ranging from using leaked credentials to accessing the environment from RDP. Furthermore, one of the most common methods of intrusions for ransomware intrusions is via remote access protocols such as Remote Desktop Protocol (RDP), Virtual Network Connection (VNC), and VPN. In our analysis, SecurityScorecard observed failed connection attempts using an RDP connection to the JBS Australia IP address space (the same IP address that data was exfiltrated from) on February 28, 2021, right before the data exfiltration took place. The source IP address of the attempted RDP connection to JBS is not associated with any known digital footprint of JBS, instead, it is historically listed as a malicious source. This indicates that the threat actor checked whether there is an RDP service running on the system by making an RDP request but did not receive any response from the server since it is not running an RDP service. This checking of vulnerable services running on the system can be an indication of a reconnaissance performed by the attacker.

Leaked credentials – breach in February 2021

In our research, we discovered leaked credentials belonging to employees in JBS Australia from early March 2021. Such credentials appeared right before data exfiltration began. The fact that JBS employee credentials are on the dark web confirms a breach occurred sometime in February 2021. The extent of the leaked credentials discovered extends to a half dozen employees from JBS Australia as part of various leak lists.

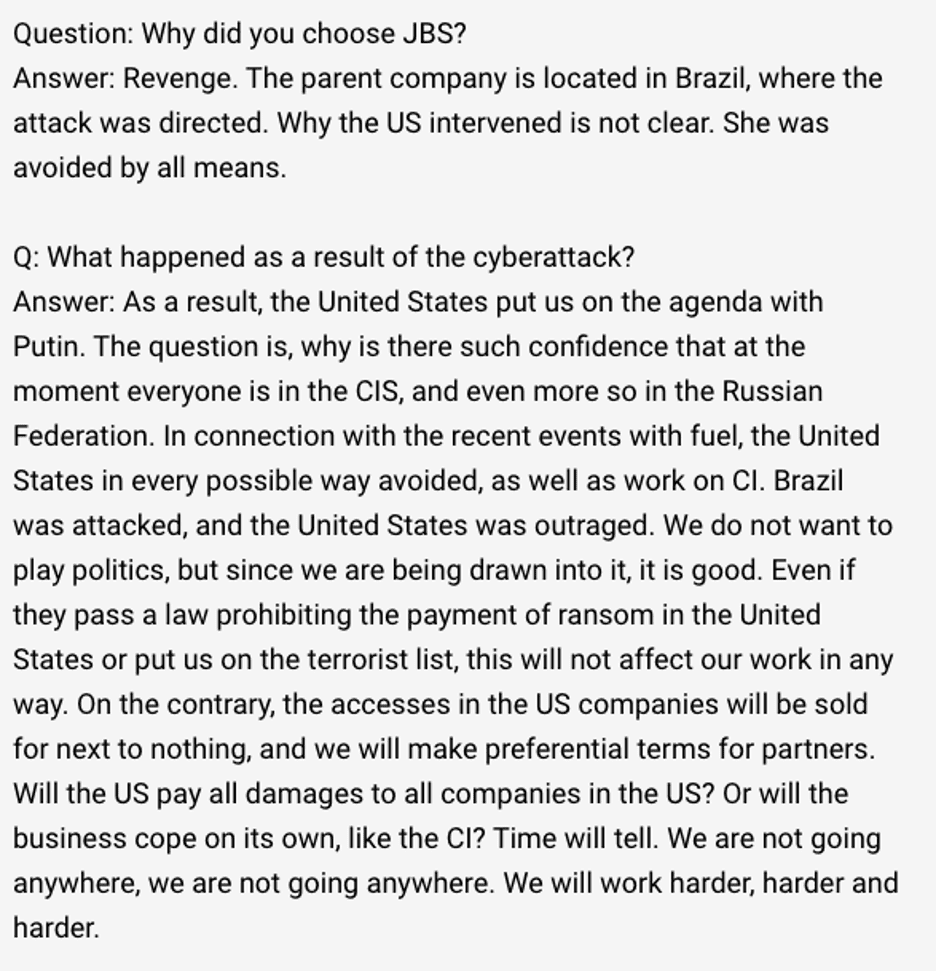

Russian language chatter

An individual representing REvil (a ransomware gang of suspected Russian origin) was found discussing the JBS attack on a telegram Dark Web channel known as RUSSIAN OSINT. The below was posted on June 3, 2021, after the attack was publically noted. The following is a translation from Russian to English of some of the interviews that transpired in regards to the motivations of this attack. According to the translation, the threat actor intended to target Brazil in an effort for revenge.

Persistent connection

During our investigation, SecurityScorecard observed TeamViewer traffic destined to an IP address in India. This might mean that the threat actor installed TeamViewer within JBS Australia’s network environment. This activity occurred during the same timeframe as the data exfiltration. The connection could have been used to maintain access to the environment. Since TeamViewer supports file transfers, some data might have been exfiltrated in this way too.

A particularly notable connection was one observed between May 18, 2021, and May 24, 2021, with a server from India. What makes it unusual is that being established through a TeamViewer server, it was left open for 5 days, and we were able to make a correlation with the same time period right before and after the data exfiltration to Mega.

Data exfiltration

As with all ransomware operations, the attackers are likely interested in exfiltrating data and potentially leaking it on the dark web if victims do not pay. Typically, the threat actor exfiltrates data before encrypting files, then uses the data to extort the victim for financial gain. Using our unique global insights, which includes Netflow, we have uncovered multiple exfiltration operations from the JBS environment since March 2021. For example, we observed exfiltration (a common method used in ransomware attacks) to the file-sharing site Mega between March 1 and May 30, 2021, in excess of 45GB. In addition, this data exfiltration is broken up into multiple smaller transfers (over a dozen) during the course of three months.

Further, we discovered that a total of 5TB of data had been potentially exfiltrated between March 1, 2021, and May 29, 2021, to assets in Hong Kong. Our research indicates that multiple exfiltration methods have been used in addition to data transfer via Mega.

Poor hygiene in the food industry

It’s not just JBS that has problems, unfortunately, the food industry as a whole suffers from cybersecurity hygiene issues. SecurityScorecard rates the outside-in cybersecurity of over 55,000 food industry companies, across factors including data breaches, software vulnerabilities (CVEs), and malware infections. On the whole, the results are poor:

- Over 20% of food companies have a known vulnerability (CVE) in their exposed Internet assets. These vary from the relatively benign to the very critical. Some of these CVEs could lead to attackers exploiting systems. The affected systems range from Nginx (common webserver) to SSH (remote access) to Microsoft products.

- We are detecting widespread malware infections. Over the last year, we’ve observed 2,444 food company IPs communicating with our malware sinkholes – ideally, this number should be zero.

- 366 companies have suffered a breach and/or attack.

- Finally, we have observed nearly 2,500 instances of products often exploited by ransomware (e.g. RDP, VNC, or Samba – all types of remote access services) on the food industry’s public-facing Internet assets.

Methodology

SecurityScorecard’s method of analysis includes evaluating multiple sources both public and private. Further, the analysis is not solely based on information in open source that can be obtained by anyone (i.e unverifiable data/sources), while open source is an element to our analysis and a data point in itself, it is not the sole determining factor. This analysis is focused on looking at the characteristics of the attack, partly using OSINT and vetted intelligence data we have obtained through private partnerships, confidential sources, in order to make our conclusions.

Conclusion

We believe JBS suffered data exfiltration and a ransomware attack, a common approach from threat actors. We can also identify a reconnaissance prior to the data exfiltration. What is remarkable about this attack is how unremarkable it was in both execution and occurrence; it illustrates just how common ransomware attacks have become. These kinds of attacks have a financial impact on the victim that goes beyond the payment of a ransom; they may need to be disclosed to customers, business partners, and likely to regulators and via the company’s written disclosures.

Any organization with Internet assets must now consider themselves a potential ransomware victim. Organizations must consider their own security and the security of their vendors and third-party suppliers.